Dado by Alain Jouffroy

Dado or the Generosity of Morning

The following text by Alain Jouffroy first appeared in no. 42 of the review XXe siècle (p. 55-63) in June 1974.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

Close to the Albanians, the Montenegrins form a minority community which during the War produced the most courageous resistance fighters against the Nazi order. People envy them all the more since their heroism was so undeniable that it became uncomfortable for everyone. More independent through temperament than through ideology, they are not ones for what are called “concessions”. Dado, who has kept his Yugoslav citizenship and who has never dreamt of benefitting from the rather ambiguous status of “political refugee” in France, has to date affirmed his position as a member of an obscure community of whose traditions the majority of people remain totally unaware. His painting asserts a fundamental heterogeneity with respect to our culture: it is perceptible only from a distance, and it condemns us, us, to the status of aliens. It is a universe from which we are excluded; it is up to us to make the effort to enter it, to carve a path through to it. I have not yet managed to gain intimate knowledge of it, in spite of the fascination Dado’s pictures have exerted on me since 1958, the year of his debut Paris exhibition. Over these fifteen years I think I’ve no more than made a number of brief forays into Dado’s intellectual heartland, and I always leave his exhibitions prey to a certain consternation – as if I feel I’m being held at a distance by a man who can have no truck with my criteria and yet who manages to move me, to disturb me, to ask me questions, without ever using a language conducive to establishing with me that wordless dialogue we call understanding.

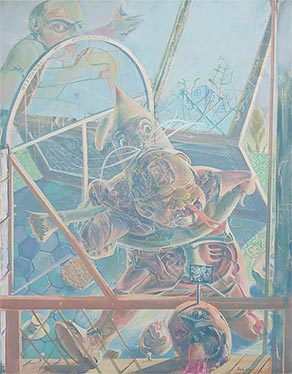

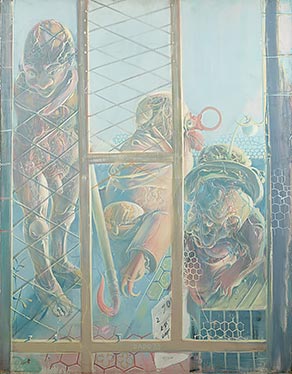

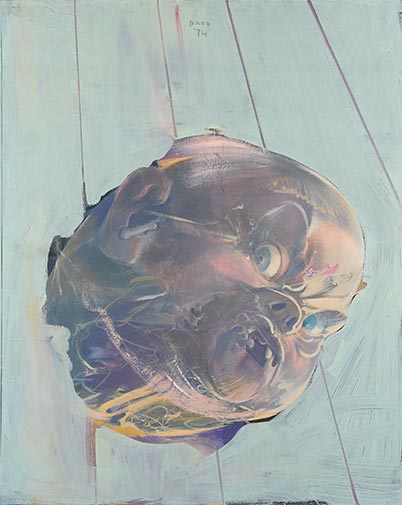

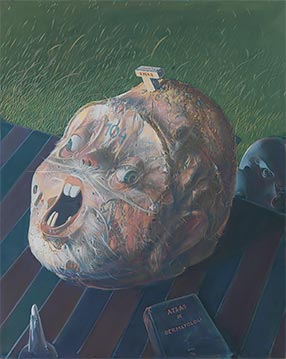

It is all very well to say that we sat beauty on our knees and spat in its face, beauty continues to slip through our fingers. We don’t know what it is. Occasionally it even wears the mask of ugliness and we suddenly notice the beauty that surrounds us, as if we had been blinded by everything that contradicts it. In the same way, with respect to pictures, most of the time we prefer to skirt over the question of their “beauty”, as if we were ashamed of acknowledging that most often we confuse this with elegance, with taste, though these terms are only expedient derivations. Dado’s paintings, however, keep us under a spell so individual that they flood the ugliness of the world with all its beauty. The two powers that govern us instinct for life and yearning for death – engage in fabulous combat, though we will never know which one will emerge as the victor. There, destruction, war, and catastrophe couple with love, with celebration, with the pleasure of getting drunk on life. It is the dark night of the tomb, with worms swarming over corpses, casualties writhing on the battlefield, amputees, monsters, idiots, and it is also the day of birth, dawn at the edge of the forest, it is the morning of knowledge, the time to enter the fabulous paradise of animals and legends.

His most recent pictures have done away with women racing out of doors and shouting “fire!” and with men thrown onto the street with their shoes, their sheets, and all their clobber, with those monsters strewn about the beach, in swimming-pools, or on the waste ground that in suburbs separates the council housing from social aloofness and avarice, and he has now taken up with emblematic birds, with fabulous beasts around the Christ of St Hubert. Thus, Dado’s “religious” thematic, which emerged at the most recent show at Jeanne-Bucher’s and which will be even more noticeable in the exhibition at the Boymans Museum in Rotterdam, is totally at odds with any kind of orthodoxy: Dado’s “Christs” are gangland bosses, barbarians, usurping princes thrown in the stocks, men who beg the people to dance around the scaffold of their torment.

There is no hint of the superiority of the divine, nor even of a transcendental “intercessor” between two worlds – instead the ever stupefying, fascinating, terrifying, aberrant spectacle of human folly: carnage, outrage, bestiality, pomp, magic, flight, frenzy, orgies, prophecy, transgression, outlandishness – the general conspiracy between every power hostile to the individual. A kind of apocalypse, where, at each and every moment, the challenge is to reinvent as fast as possible all living beings – things, plants, stones, the sky, animals, even matter itself. Outside time perhaps, or rather in that eternity that binds prehistory to the modern world and the most primitive needs – hunger, thirst, the instinct for self-preservation – with the most complex findings of the intelligence: the ritual of thinking, the ceaseless decoding of signs, the transformation of forms, the unstoppable metamorphosis of thought.

For a few years now, Dado has been capturing light, the light that flits over things, as perhaps no-one has ever seen it before: a four-in-the-morning summertime light, velvety would be an understatement, yet ash-grey, like the wings of certain butterflies, those that live for a single day, for a few hours, amongst the flowers that have just blossomed and the fog that has just risen. It is then the most distant of philosophies that illuminates these magmas, this debris, this gigantic jumble – the philosophy of reserve, of isolation, of extreme reticence. The world is unacceptable, that we know, but when thought casts its light, it transforms into signs, into portents, into premonitions of the marvellous. And finally there is this immense gentleness that descends on the empire of disorder, recreating a space for peace between the dislocated limbs of the combatants, among the corpses and the survivors from conflagration, flood, and distress. Yet, though gentle, nothing is left out, nothing censured: atrociousness is there, but it is countered by the infinitesimal glory of a man who knew to turn his painting into the boundless province of generosity.

Alain Jouffroy

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz