Dado by Alice Bellony-Rewald

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

This text by Alice Bellony-Rewald was first published in December 1973 in the number 15 of the review Colóquio published by the Gulbenkian Foundation.

This text by Alice Bellony-Rewald was first published in December 1973 in the number 15 of the review Colóquio published by the Gulbenkian Foundation.

Opposite, Dado and Alice Bellony-Rewald at Hérouval c. 1975.

A perfectly uneventful childhood in Yugoslavia, in Cetinje, a small town in Montenegro. Youthful escapades in the arid hills covered in rosemary, teeming with wild goats. A family, essentially normal enough: an uncle who was a painter, another a doctor, auntie Julie, her son who went missing in the Resistance; an ambitious and severe mother, the father less so. Historical memories haunt ancient memories and reach his ears: exquisite massacres undergone or perpetrated (well before he was born) during the Turkish occupation. The war on everyone’s lips and which he encounters on a road in the form of three eviscerated horses rotting in the sun. Death, like a picture from a chapbook, which sets one dreaming: the death mask of a cruel and powerful pasha assassinated by brave Montenegrins and preserved under glass in a splendid castle. Strong impressions, imprinted by chance, that later turn into obsessive images.

Then, another, more decisive death: that of his mother. He is eleven years old. He leaves school and hits the road.

At fourteen, he registers at the Fine Art School in Herceg Novi. He is destined to become a painter. His mother told him so one day, shortly before she died. He was struck by what she said: “You’ll be the Walt Disney of your generation”. He thinks so too.

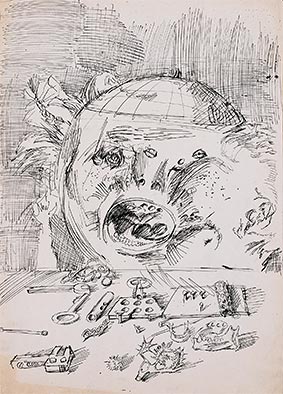

Right: Cugo, 1955, ink on paper, 41,5 × 30 cm. Formerly Jernej Vilfan collection.

Photos: Domingo Djuric. (Cugo was a friend of Dado whose father was a locksmith. qv. infra.)

By 1952, he is in Belgrade, on the roll at the Academy of Art. He is nineteen years old. He frequents a close-knit group containing some of the most gifted artists and intellectuals in the capital. They deride the authoritarian government. They give one another a helping hand and encouragement, all the while looking westwards, where freedom of expression rules.

Since the First World War, a fully-fledged artistic movement has emerged from Montenegro, which, benefitting from government support after 1945, fulfills a notable role in contemporary Yugoslav art ¹; its most outstanding representatives were exhibited in Paris in 1953. Miodrag Djuric, who that very year is just twenty, shows two canvases, as does his elder brother.

“My first pictures were mechanical pieces, such as The End of the World or The Cyclist. They came straight out from when I was a child and spent time with a pal of mine later killed on Lake Skadar. His father was a metalworker and every Saturday afternoon he’d come and get me to tidy the workshop: adjustable wrenches, pincers, things to weld tin, to weld pans. There were planks with nails on the walls on which we had to hang dozens of tools.”

The works exhibited a few years later in Paris betray nothing of the mechanical, constructivist influence of these very early works.

Photo: Domingo Djuric.

It’s true that on his arrival in Paris in 1956, Miodrag Djuric’s life was to undergo an almost complete transformation that forced him to set aside all his experiences and habits, leaving him as vulnerable and helpless as a baby. To survive, he had to swap his mother tongue for the arcana of the French language as fast as possible, to give up the measured pace of the almost provincial life of a Balkan capital and join that battle that is the life of an impecunious foreigner in the French capital. He also has to trade in the asperities of his exotic name for a less daunting pseudonym of just two syllables, Dado, and turn from a student into a workman.

“In Yugoslavia, from age fourteen to twenty-two and until my arrival in Paris, I’d never worked half an hour. That’s how it is in Socialist countries, you’re given board and lodging. In Montenegro one had even brushes.”

For the first two years of his life in Paris, he started out as a house painter. Then, he found work as a jobbing lithographer. “I had my drawings and a few pictures hanging in a corner of the workshop…” They were admired by James Speyer (of the Art Institute of Chicago), likewise by the painter Dubuffet.

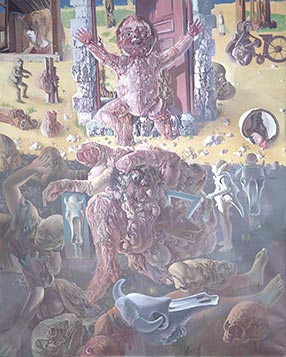

Dado’s first exhibition was organized in 1958 by Daniel Cordier. It mostly featured babies; distressing accumulations of homunculi or else just a single one occupying the entire picture. They were perversely deformed: in one, for example, the foreground presented its buttocks, anus, genitals and the fleshy balls of its feet. The compacted torso was dominated by the puffed hillock of its cheeks with ensconced in them a tiny mouth and nostrils, as well as two goggling eyes. Its form seems to have been blown rather than modeled by the brush, and bathed in a thin juice of poisonous colors, pink, gray, very pale blue. The choice of subject and treatment were disconcerting. Asked, Dado answers:

Poets and writers might cast more light on his methods. Henry James, for example, writing that: “The natural inheritance of everyone who is capable of spiritual life is an unsubdued forest where the wolf howls and the obscene bird of night chatters.” An heir gifted with a singular temperament, avid of knowing his full potential, an explorer subjected to powerful iconographic demands – perhaps, in his pictures, Dado is delineating a state of his inner world.

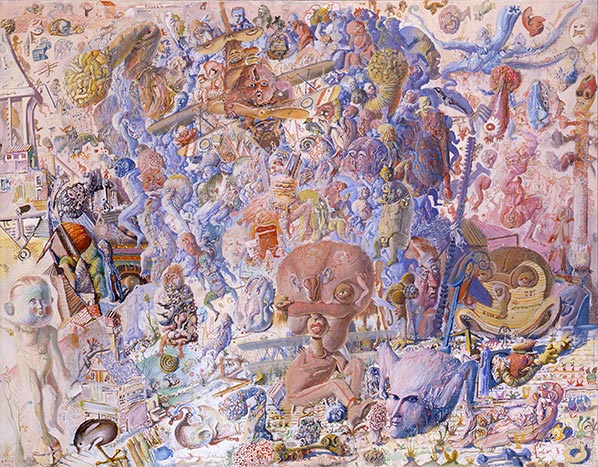

Between 1959 and 1963, the infants are replaced by vast compositions. No less surprising, they catch the eye with their cacophonous pictorial orchestrations of a decomposing world whose delights and impurities betray a deeper disorder. These are disturbing, seething, airless landscapes, a mayhem of swollen-limbed djinns, of blighted goblins, cruel gnomes who, with a frenzy verging on the sexual, probe into the flesh in the search of some unheralded suffering, ripping open bellies that they fill with stones, mutilating genitals, playing ball with children’s heads. This apocalyptic universe that seems stiffened in fear betrays loose links with the art of the Middle Ages, of that Middle Ages that images of the time show obsessed with pandemonium, with disjointed worlds, with monsters, with the infinite diversity of the torments that await us.

The admirable confusion, the rhythm and movement that reign in Dado’s finest compositions recall some extraordinary graphic composition illustrating the Last Judgment or the Temptation of St. Antony. In both, one sees naked bodies, skeletal or puffy, twisted and convulsed, strung into bunches, at grips with monsters of the dark, with gigantic toads or pustulating reptiles. Certain parts of Borovick or The Large Farm ² somehow relate to the seething mass of damned souls in the foreground of Van Eyck’s Last Judgment. Among all these angst-ridden, pressure-cooker works though the occasional capriccio appears to exemplify the variety of the artist’s inspiration. For instance, in Thomas More and the portrait of The Architect, both from 1960, and in Catherine of Russia (1958/59), the artist – like a consummate alchemist – reproduces with diabolic minutiae every crack, pustule, rash, excoriation, and pleat of the skin, every fissure and lamina of the stone, to the point that the qualities of one kingdom overlaps with those of the other.

Arid colors, brownish or grisaille, with the odd bright or pastel highlight, ooze over the entire surface of the canvas to a perfectly smooth sheen; owing nothing to impasto, the accidents of stone or flesh are depicted in trompe-l’œil. The ambivalence is total.

The macabre accumulation of decapitated bodies composing The Polish People (1959) was carried out in this fashion, and the mind is immediately set in train by its visual shock: the eye, if playfully at the beginning, soon exhausts itself in drawing up a madcap inventory, trying to identify in its wrinkles, its leprosy, its affliction of each stone-cum-face in the building. The figure in The Fall can be distinguished from the wall against which it leans only by the bluish tinge of its silhouette; the rest of the picture is entirely in gray monochrome.

The decade 1959 to 1969 proved extremely productive and Dado was frequently exhibited in galleries and museums in Belgium, Germany, Canada, Switzerland, Sweden, the US, even in the Indies. As he sometimes shared a room with Surrealists of the first generation, such as Ernst, Brauner, Tanguy, and Magritte, attempts were made to link them, but he feels few affinities, preferring “the extraordinary genius of primitive art,” Fouquet’s Virgin in Antwerp, Durer, or the Flemish Renaissance. “The painter who has fascinated the most,” he confesses, “my first paintings betray his influence, is Witz ³. It is from him that I gained the most, and this is very little known. I’ve never seen actually his pictures, but the drapery, architecture, the details, it’s very beautiful. No, Bosch, it’s as if it were painted yesterday, terrifying virtuosity. Bosch was obviously pulling our leg.”

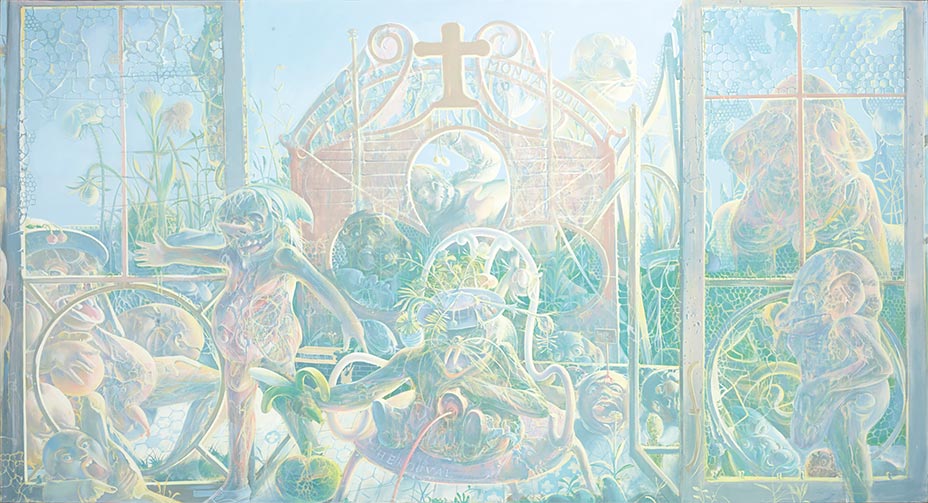

The pictures he shows in 1971 at the Jeanne-Bucher gallery were less obsessive, less highly-charged, and the sky, formerly absent, now occupies a significant portion of the space; air circulates between the various planes, while elements borrowed from the everyday routine – shoes, bottles, chairs, – rub shoulders with teratological fauna.

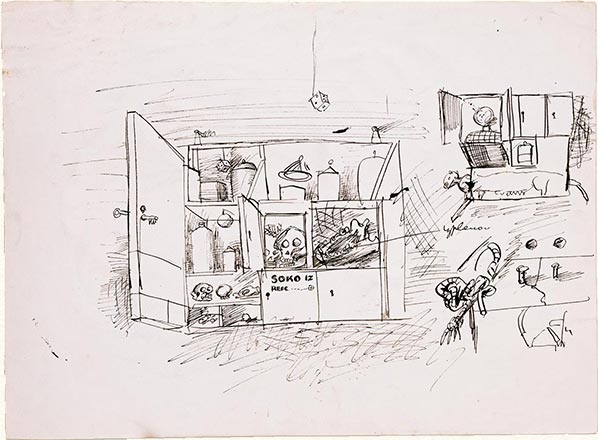

These objects derive their fantastical nature from their proportions, deliberately distorted in relation to other elements in the composition: this is the case with the tiny house in the Letter to Madame de Sévigné or in Štirovnik, for instance. Architectural details, like floorboards or flagstones eaten away and splitting on the ground, fulfill an at once decorative and structural role; parallel vertical lines indicate the depth of field (in The Studio), or horizontal and vertical lines (in The Swimming Pool) map out the distance between the scattered groups, while the texture of the more or less understated materials forms a lattice that connects otherwise isolated subjects (in The Children’s Room).

Reality is incorporated more directly, less seamlessly in pictures from the last two years, and often seems more agreeable than the imaginary world. Self-portrait in Quicklime, the Triptych of Pali-Kao, and the Self-portrait with the Clap feature the same decorative arabesque, a kind of rosette or cross, whose ornamental value is picked up in this last-mentioned picture by the curved armchairs and garden seats. In Cemetery at Montjavoult, a central ornamental theme is gracefully accompanied by the highly imaginative outline of the vegetation in the foreground. Like so many others, these motifs derive from the artist’s entourage, retained solely through some weirdly selective visual memory. The cruciform trefoil in these latter pictures, for example, was borrowed from a wrought-iron grille recently erected in the mill at Hérouval, where the painter has been living for about fifteen years. The doors opening into the void or delimiting the tumbling walls in The Kitchen of Mother Gérard and in Vesalius’s Bad Pupil date from the time the artist had just acquired the ruined mill.

Such elements, whose appearance in the painter’s life can be dated, constitute important pointers for a chronology of the oeuvre (neither always dated nor entitled), because they seldom appear in just one piece, but generally recur in a series of connected pictures. It is otherwise impossible to distinguish any veritable evolution in his career, since from the very beginning his skill has been unquestioned; however, changes in palette and composition are frequent, while certain themes are reworked or reemployed. These shifts though remain unexplained: “That’s what worried me at the time. Why was it? It’s a question of mood,” Dado explains. In fact, a slave to his inner visual obsessions, he puts them through their paces so as to exert mastery over them.

With each successive exhibition, Dado’s pictorial process has become demonstrably more personal. On the margins of present-day movements when he showed for the first time fifteen years ago, he still is, in the sense that his great technical knowhow and virtuosity sets him apart from his contemporaries. Formed at a very young age in a country where art serves to provide a moral illustration of events, where a masterful technique is synonymous with aesthetics, he could in all innocence absorb the tricks of his trade without chafing at the constraints. He now uses what he has learnt not as a rebellious intellectual but as a skilled craftsman.

Painting quickly, he nonetheless complains of the length of time he spends on each of his large formats – “six months, sometimes eight,” he says, – because, often, the picture can be painted, unpainted, and repainted. A triptych three meters by nine was in the studio ready for shipping, and yet the following week it was still there, but entirely recomposed and repainted.

“A painting that really possesses a life of its own has at least ten pictures inside it. It’s been finished ten times and it’s the tenth that counts. Finally it radiates the ten obliterated pictures.” Although often subjected to repainting, his works, especially the more recent, remain astonishingly fresh. Their delicate colors impart an impression of lightness and transparency, so the doe-eyed vampires, lascivious old men, scrofulous fetuses, and divers monsters alike eke out a life in an atmosphere seemingly chemically distinct from ours, the diffuse light coming from an invisible source (the pictures have no truck with shadow), a fact that makes these worlds appear even stranger, placing a welcome distance between them and us. “I obtain these effects by laying in thousands of tiny touches in different, invariably very pale colors extremely close to one another; these dots blend into a single, overall hue more saturated than its components, creating the impression of a uniform surface. And yet, if you look closely, there’s not a square centimeter of canvas covered in just the one color.” This loosely resembles the theory of optical mixing practiced by Seurat, Signac and sometimes Pissarro; there is no need to say how slow this process can be.

“If I’d lived elsewhere, my colors would have been different; the light of the Vexin has made a great impression on me,” the artist affirms. His residence at Hérouval is close to Éragny and Pontoise, the Impressionists’ favorite hunting-ground. During the summer months, the color of the wheat reflected by a sky of intense blue is contagiously blond. Based on his pictures, one would think the painter’s imagination inexhaustible. But he claims to have none at all and attacks his pictures without preconceptions: “the composition is never formulated in advance in my head; it comes to me when I have a brush in my hand.” On the blank canvas, with a brush scarcely moistened with paint, he rapidly installs vague forms in colors that are never final. To outfox the blankness of the canvas, he draws sibylline inscriptions, or his name, or his telephone number. These will later disappear, though in recent pictures figures appear carrying a price-tag stuck to the end of a long pole, like on a stall.

Although a first-rate draughtsman, Dado does not employ preparatory drawings: “No, my drawings seldom relate to a painting. Moreover, I almost never draw anymore. I did many drawings on my arrival in Paris, continuing later, but this was above all for financial reasons. Now, I prefer printmaking and lithography.” These early drawings were often large formats as thoroughly worked as his pictures. A painter by vocation, Dado is a poet by instinct: the titles of his pictures are visionary, combinations of sonorous, exotic, evocative words, and never descriptions. Yet he opines:

“I don’t care about titles, they aren’t important to me. But they must have one so they can be told apart, so I find titles nowhere and everywhere; they’re associations or words or things that stuck in my mind while I was working on a picture. For the Thomas More, I had a neighbor, Father Gérard, sit for me once or twice, and I could have called it portrait of Father Gérard.” All well and good, but “Descartes, who’s that?” could be Dado’s motto as he turns his back on logic and sets his course for what’s most important to him: painting, poetry, suffering, love, life, and death.

One of his close friends recounts how, having just moved in and shivering in the ruins of Hérouval, he sent someone to buy a sheep – as someone else would a blanket, – to which he held fast, day and night, to keep warm. This shy, bushy-haired Bohemian with the gentle yet twinkly look defies description – just like his painting, which requires lengthy examination to discover whether one likes these images that “make organs come to the surface and turn one’s sensibility inside-out like a glove ⁴”.

Alice Bellony-Rewald

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz

1. “Art Moderne du Monténégro, 1945/1970,” exhibition at the Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris, May 1973.

2. In 1961, a close friend of Dado’s, Réquichot, killed himself aged just thirty-two. He was a gifted artist and a major retrospective of his oeuvre was held at the C.N.A.C. last May [webmaster’s note: that is, May 1973].

3. Konrad Witz (1400?-1445?): celebrated Swiss painter and predecessor of Holbein. An unfinished Redemption and a Christ Walking on Water.

4. Antonin Artaud, Les Tarahumaras.

A number of quotations have been taken from Entretien avec Dado, published by the C.N.A.C., Paris, 1970.