Dado by Henri-Alexis Baatsch

The Dwellers of the Prairie

This text by Henri-Alexis Baatsch initially appeared in the third number of the journal Fin de siècle in January 1976.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

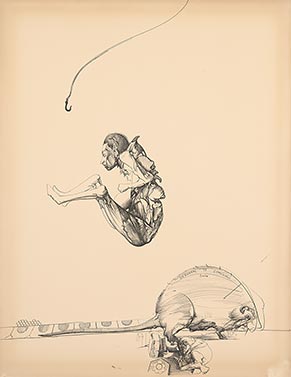

I returned without my weapons, deathly joyous, drunk with laughter, from the salon of Ivan the Terrible. Seen from the point of view of the dead, from the gray innards of a crocodile, tyrants, more than the rest of humanity, harbor the ineffable secret of buffoonery. Pregnant with emptiness, outlandish in their absence, languishing in drying blood, impotent in their smiles. Their couches are so small and the world so vast. It seems there’s a skylight in their flesh that’s more real than elsewhere, a hole forgetful of man’s condition, which issues invitations to visit them as one would a museum of disease, a museum of paleontology or zoology. All the best tyrants are small and deformed, scrofulous, with a taste for anemones, subterranean eyes, toucans’ teeth, apish aspirations, chattering false-teeth, attic-storey obscenities. Death lurks within them, and the most remarkable thing is that they remain blissfully unaware of the fact. And yet their eyes could take in the entire horizon; their beds are like carapaces, and deep in their orbits the seminal fluid builds up, they imbibe great cupfuls of an herbivorous creed from Catholic troughs.

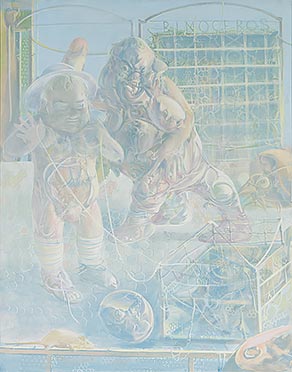

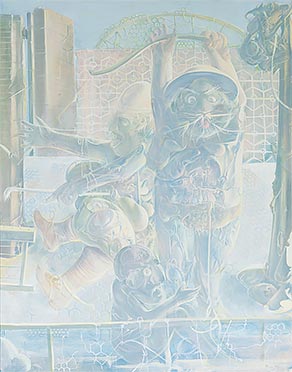

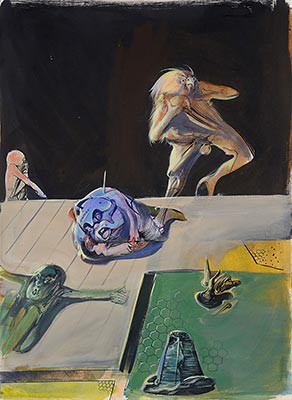

Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger. Photo: Jean-Louis Losi.

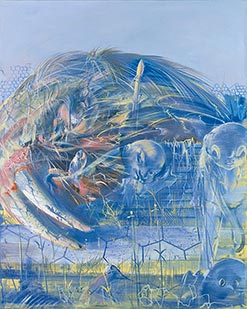

Death-dodger, Oh, skeletons that warm the heart, you, sneering domestic divinities of China, livid, vast, corpulent, there are pockets in your skin chock-a-block with faces and groupers, a black panther with a parrot’s beak severed without ado from life, a circular wraith from a viscous savanna.

Like a bearskin which, too large for our use, seems to contain a body, or several bodies, without really belonging to them, or like this remark Lichtenberg scribbled down: “He found it wonderful how cats’ fur has two holes exactly where the eyes go”, the poetry of monsters knows no end. To general amusement and terror, they engender one another as far as the eye can see – unrecognized even to each other, passing unhailed, impassively unfurling their pink entrails, caring not a jot for death; in the subtle azure of a rising sun, they reach out their tongues to lick the ground and devour one another, whittling away at their genitals to rattle the world. Their cries turn blind in the silence of painting.

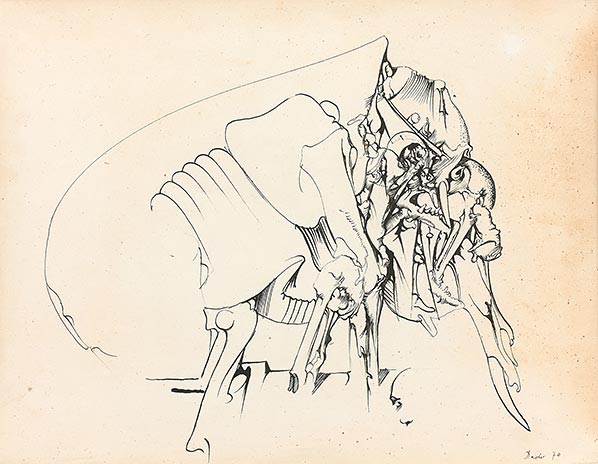

Because of the horror it sows, or tries to sow, it is natural that human power be depicted in monstrous form. The Middle Ages believed more in its demons that in paradise, while Hieronymus Bosch knew more about demonic delectation than about the hell of delight. Savage fetishes, ancient divinities – excepting for the Greek world whose delirium lay elsewhere – all too often represent grimacing, destructive beings and, in early cosmogonies and mythologies, serene figures remain few and far between. The phantasm of chaos constantly resurfaces – and that phantasm is chaos.

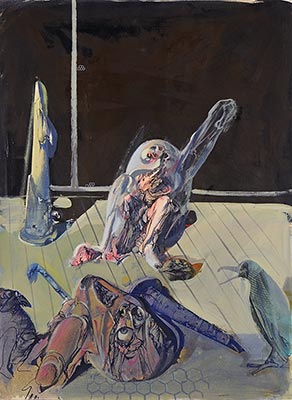

Courtesy Galerie Jeanne Bucher Jaeger. Photo: Jean-Louis Losi.

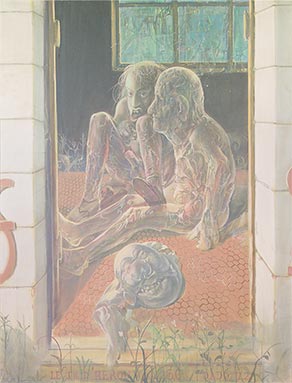

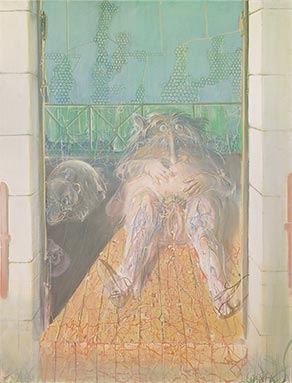

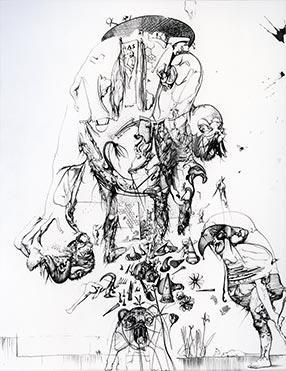

Be it by the title alone, the Triptych of Pali-Kao, or by the grotesque figure it conjures up for me, or by the derisory crucifixion of phalluses and vultures, – exaggerated excrescences of bellies and skulls, – I see Dado’s depictions as the joy and recovered fruitfulness of chaos and of natural disorder. A virile power, the bloodstained power of the cross held over the world – an animal power, the power of indistinct forms and of the night of the mind, – all various manifestations of that power that erupts invoked by the hand that paints, emerging, one by one and in a special kind of trance, and “straddling” (as servants of voodoo divinities express it) the one who lies in wait for them at dawn, not knowing what will appear in the unprecedented glow of that day, nor whether he will really be able to capture their form and attributes, certain only that someone will come, because vision is infinite and unceasingly renewed, and that the human and psychological tradition to which the painter bears witness has already made of this fantastic, as yet unfashioned being a luminous reality that no mask can conceal.

Life is a fine tale: like a skein of frogs flapping out of a mass-grave at one’s birth.

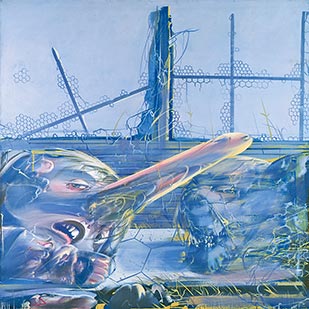

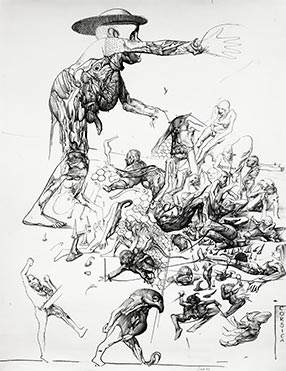

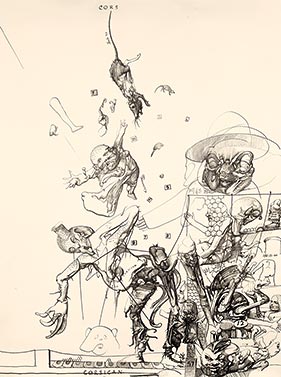

Right: Corsicana, 1973, ink on paper, 66 × 50 cm.

Beyond the body, the frenzy of its parts. Beyond light, the shadow of light. Beyond death, and on this side of death, the onset of decomposition; that atrocious interlude of what was and is no more; unrecognizable, yet not unknown. Beyond joy, the ferocity of being. Beyond passion, placidness, imperturbability before the world. In the land of beamish phantoms heaped up on the grass, beckoning a dawn of light and movement without end, Hérouval, studded with grotesque crosses, adorned with skin diseases, the nec plus ultra of the Darwinism of vision, where unaided monster morphs into monster – as, through time, in the passage from unicellular to man. The frozen genitals of a mammalian eagle glories over an orgy of corpses. The cosmic camel brushes its hump against the crest of the waters; thus the origin of waves.

The sleep of reason engenders monsters; the sleep of monsters engenders unreason. Medieval musings show a fondness for monsters and chimera, but, as far back in history as we go, no civilization, no speculation has ever been exempt from hell. The school of monsters is a dream with a future. I quote this example only because I have been able to verify it very recently, in an unexpected, surprising, and even dangerous fashion. I might have expected it in Egypt or among the extravagance of the Incas, in the world’s most anthropomorphic visualizations that affect the tiniest objects: vases, broaches, fountain basins, the symbolism of frescos deployed ad infinitum over the walls, enclosed on themselves, like the tomb gazing out at them. But how much more astonishing to find it in one of the rational outbursts of the Italian Renaissance; in the decoration at the Palazzo del Tè in Mantua by Giulio Romano, where mythology is deployed to shake the senses to their foundations, in the exaggerated erotization of the glacial and of gigantism, in enfilades that disappear into a collapsing world, in grimaces unceasingly adopted then abandoned, in misleading looks, in crushed cheeks swelling of their own accord, betraying the senses and already laid waste. A world without monsters is a lost world, a world that forsakes for evermore the unutterable charm of the pipedream, thus severing the ties that bond it to man, to the realms of the otherworldly, to night and to day.

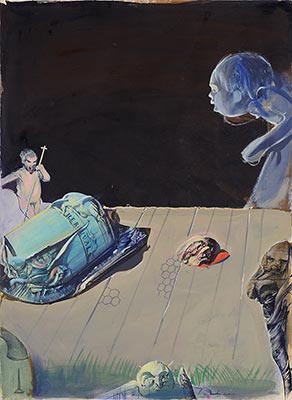

65,5 × 50,5 cm.

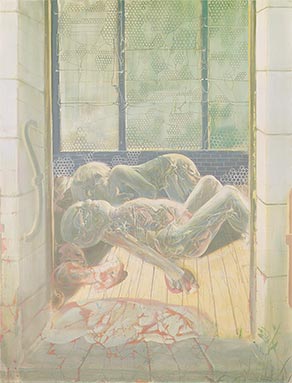

When observed an eye becomes the ideal screen for revealing, for concealing, the magic moment; the enormous sphere of its white expands to unconscionable size and the sweeping curve it describes overruns everything, filling for an instant all space. Perhaps something of this emerges in the art of swirling flesh that Dado has invented. There, the transparency of the body, the limpidity of the brain, together with the manifest description of its internal workings, a new “art of the portrait” (and any monster with this name is a figuration of the human, a contribution to psychological anthropology), all cease being mere words. Dado populates the space in a quest for knowledge – the same that governs the ritual murder of bulls in Ethiopia and the invocation of spirits beneath the veil of the animal’s mesentery stretched out above the heads of the officiants.

As the saltpan slumbers, hybrid gnomes appear at the surface of the water, of the fields, loud sagacious cries of tortured gods go up, all the calm of a finally inhabitable nightmare. The potential for flight and overflight, for retraction, for the diffraction of a pullulating universe, the convex, concave, organization of space, and, to the rear, a perspective without real depth, are exacerbated in collages from which even the illusion of a complete world has been excised. In the gray or black dust from attics razed to the ground, anatomical offcuts reconfigure in the daylight, the grass hiccups, besmirched by insects and winds. Heart of an ostrich, a worn-out gate now shuts off access to the outside world solely in the imagination; tongues from breeze-blocks, rats from remote papers, glances from stabbed rocks, meeting in the midst of cellars in the gleam of basement transoms the hairy joints of monkeys with prominent anuses of scarlet and purple, vegetate and scoff, scoffing at us from a great height and the great light of a world to come, or perhaps already glimpsed.

Henri-Alexis Baatsch

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz