Dado by Michael Peppiatt

Two texts by critic and art historian Michael Peppiatt, selecting curator for the Dado exhibit representing Montenegro at the 53rd Venice Biennial in 2009.

The first text, Dado, black on white, initially appeared in the brochure published for the exhibition of engravings by Dado at the Jeanne Bucher Galerie (Paris), from May 14 to June 14, 1975.

The second text is a conversation taken from the catalog published on the occasion of the exhibition of drawings by Dado at the Isy Brachot Galerie (Paris) from November 16, 1978 to January 6, 1979.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

Dado, black on white

On first meeting, and long thereafter, it remains hard to square the man Dado with his fantastical imagery. A pleasant companion, who adores tramping the streets of great cities, sociable to an extreme, clubbable and open-minded, he scarcely resembles the morbid and haunted recluse his art brings to mind.

Already convincing enough during an afternoon spent between sidewalk and cafe, the impression one may have got the wrong artist is accentuated at his home in the country. Going to Hérouval, where Dado has lived since 1960, one is ready for anything – lugubrious disorder, accumulations of painstakingly preserved grotesque, – except for the absurdly tender Vexin. Having seen Dado amongst all this cheery beauty, surrounded by flocks of children and animals, following him from pond to rose-garden and into the half-timbered studio, one harbors still greater doubts as to whether it is in him, and here, that such phantasms of terror can be born.

Little by little, however, his true obsessions percolate through. He sees the canker in the rose. Health, according to him, is just an interval before disease, like life before death. The Jekyll-and-Hyde Montenegrin’s eyes light up and his voice takes on an undercurrent of warmth. He starts speaking of disasters, about everyday brutality and stupidity. He ponders what others in general prefer to pass over in silence. He waxes tender at the sight of a galloping acne, he warms to the subject of collective masturbation at school in Yugoslavia. He is obsessed by the most vulnerable aspects of life. One might think that next to him on the table lies not a beefsteak but an instant of death under the knife.

In cahoots with his creations, we are not too concerned as to how true his stories may be; we understand that reality itself seems such a disaster to him that it allows of plenty of exaggeration. For sure, the cruelty of existence was branded into him early. He still speaks, for example, of the death-rattle of an old man who died beside him in hospital; of men in the resistance publicly hanged and displayed for several days by the Germans.

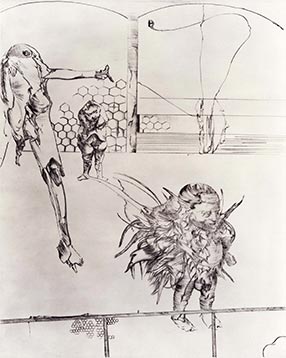

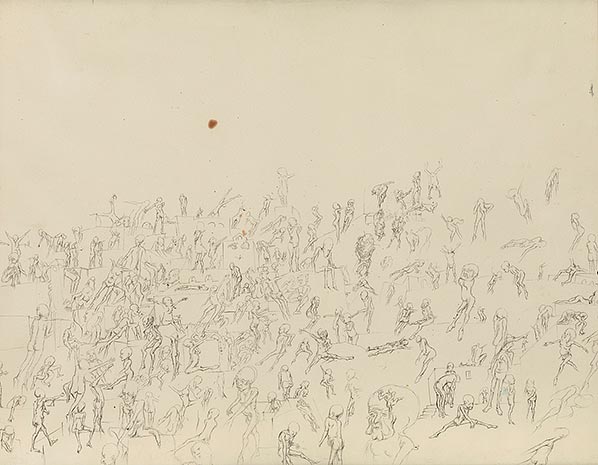

Horror and fear have been rooted in his life from the very beginning. And he emphasizes, reinvents them in his art. From them he derives his baroque tours de force, pushing them to new limits, refining every detail so that it hits home even more insidiously. His obsessive activity has spawned a dreadful, pullulating family of the limbless, the debilitated, of sumptuously limned monstrosities. They are all actors in on great inhuman comedy, exacerbated to the ultimate stage of degeneration, where what remains of life already partakes of death.

Flesh slides off the bone; new wounds gape. Curiously, the atmosphere is less despairing than the condition of the victims would suggest. In spite of the maniac variety of tortures they undergo, flashes of humor – sometimes of obscene gaiety – surge forth. Behind them, in a serene sky, one makes out the echo of a raucous, mocking laugh.

Dado concerns himself above all with the visual exactitude of each work. Flesh is not only the most receptive means of communicating his innermost sense of life; it is also a kind of malleable pictorial paste. In a material so close to us that any genuine invention would only wound us further.

∗

∗ ∗

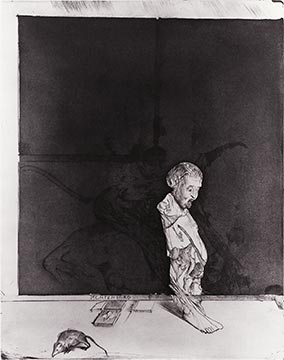

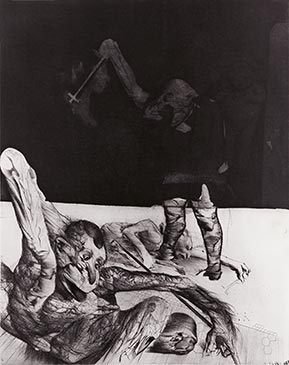

When this “kindly executioner” (as Dado dubs himself) pursues his victims with graver in hand, the same obsessions – as one would expect – take form, but they are conveyed with still greater intensity. The horror, the grotesque cruelty appears more concentrated, more straightforward. The guiltless empyrean of the Vexin is definitively eclipsed; on these bodies, a gray gleam engulfs the dewy rose. Here all hovers between utter blackness and the even deeper nothingness of white. Issuing from these two extremes of color, the scenes of degradation acquire increased authority. Staggering in this night of ink, materialized from this bleached vacuum, the figures present themselves with factual power.

Dado engraves as he paints: he starts off with an image, then reworks and transforms it ceaselessly. In a single engraving, months, years even, can pass between a first or intermediate state and the final version. The composition is often entirely reorganized, to the point that a plate can flip from vertical to horizontal, and hardly a detail of the initial composition subsists. Several of these palimpsest plates conserve, gouged into the metal, the history of their mutation. In the black ground, beneath the layer of resin in which they are entombed, pale silhouettes of rejected images still lurk, as in a shattered looking-glass.

Expressed thus, black on white, the vision strikes us by its sober and unmediated acuity. Where Dado’s painting surfaces from an infected flesh, his burin delves deeper, excavating, scarring the body like the very agent of the disease. It teases apart, excises with the insistence of the surgeon’s knife. Through such subtle interventions, the bodies become more fragile than ever; their flesh wafer-thin and seems to have been woven, like a cobweb, around the bones.

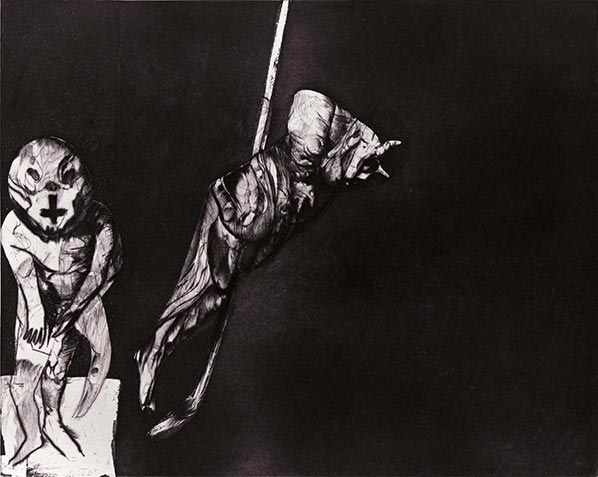

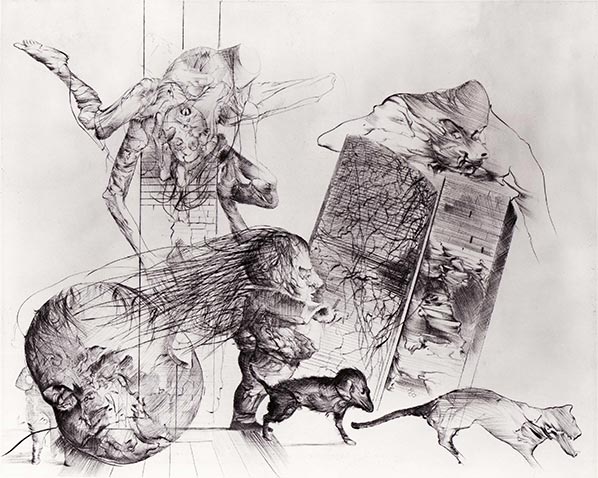

Right: The Manipulator II, drypoint and aquatint, 38 × 50 cm, 1973. Alain Controu, printer.

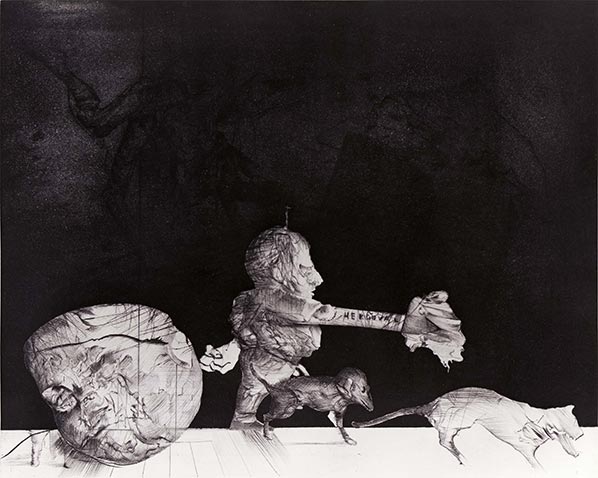

Right: Drunkard Beating a Child II, drypoint and aquatint, 50 × 40 cm, 1974. Alain Controu, printer.

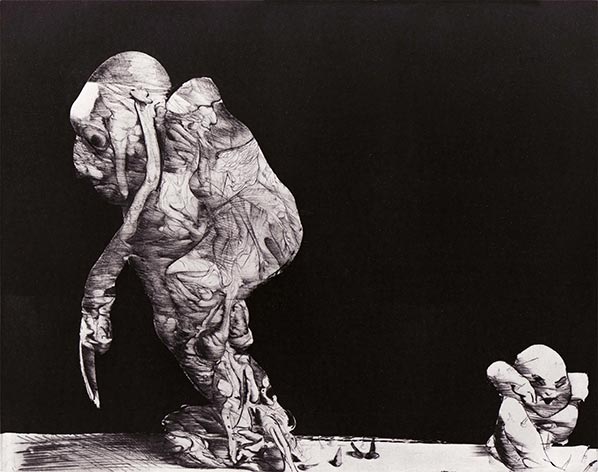

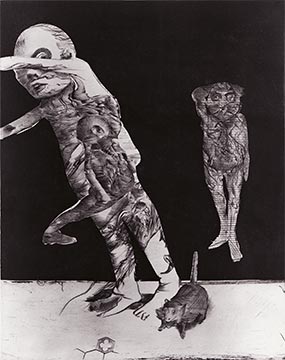

Right: Montenegro II, drypoint and aquatint, 48 × 38 cm, 1974. Alain Controu, printer.

Within this digest of putrefaction, only a few alert rodents and a select band of objects seem capable of survival. An elegant iron chair stands bolt-upright beneath a body decomposing on it, probably for some years; the room in which children shatter like porcelain statuettes remains miraculously intact. Only the grilles to which Dado frequently returns imitate flesh, dying off in little sections, peeling like living cells.

In spite of such technical constraints, Dado forfeits none of the fluidity shown in his painting. Or rather he has managed to recreate it, through the consummate mastery of every resource of his trade. Such unusual plasticity depends singularly on the range and subtlety of his colors: on the rich, velvety black, as well as on the corrosive pallid gray. Such technical success (it cannot of course be separated from the artistic success) results from years of close cooperation between the artist and his printer, Alain Controu. Since 1967, the year in which Controu first interested Dado in gravure, they have worked together regularly, extending their technical frontiers and developing tools that are more flexible and better adapted to the works’ constant transformations. No part of the output of one would have ever come into being without the other. This is why this exhibition affords testimony not only of the invention and prowess of the engraver, but also to the expertise and passion of the printer.

Michael Peppiatt

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz

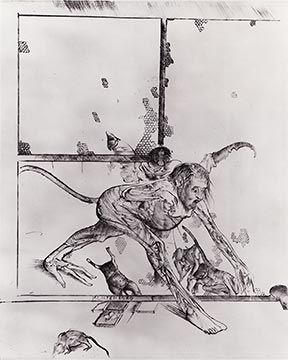

Right: Rhinoceros II, drypoint, 50 × 40 cm, 1973. Alain Controu, printer.

Right: Clap, drypoint, 23,5 × 17,5 cm, 1973. Alain Controu, printer.

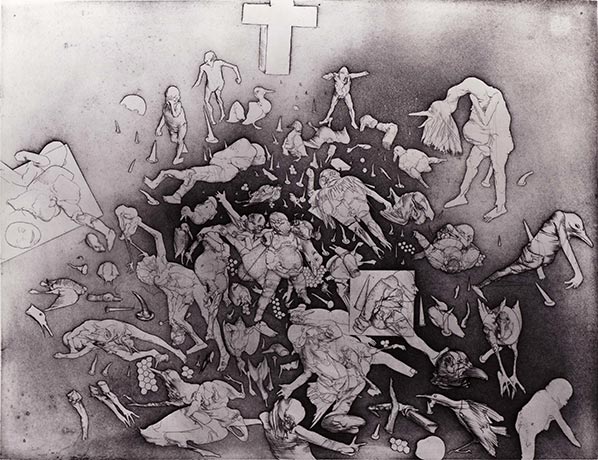

Right: The Way of the Cross II, drypoint and aquatint, 48 × 38 cm, 1974. Alain Controu, printer.

Right: Rhinoceros V, drypoint and aquatint, 47,5 × 37,5 cm, 1974. Alain Controu, printer.

From a discussion with Dado

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Photo: Jacques Faujour.

This conversation interlards and summarizes three separate interviews. The whole was recorded on tape, but, like a literal translation, the following transcription has let slip many a nuance. The ironic emphasis, the hesitations, the nettled self-esteem or well-meant tease, all the horseplay between a hunter-of-copy and his prey (who might want to be taken, but on his own terms.) disappear once couched black on white. The frequent laughter too has evaporated, as have the gestures, the little winks. Readers will have to supply these for themselves, so as, perhaps, to give life back to what were off-the-cuff remarks.

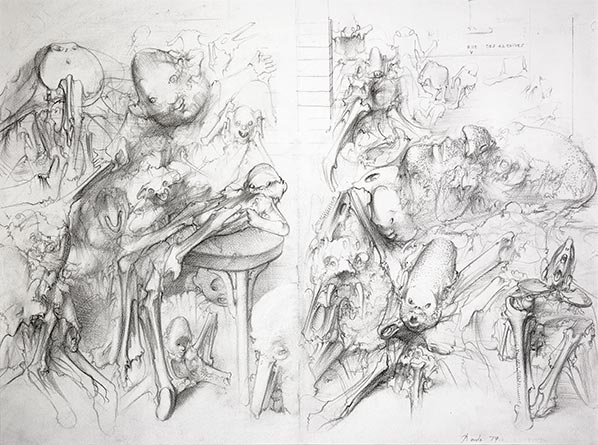

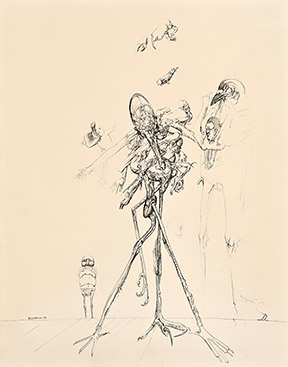

Dado: I’ve been drawing practically every day now for two and a half years, especially when the light is fading, as evening is drawing in, or at wintertime. After the graft of a large oil painting, pen-and-ink drawing was supposed to offer a kind of rest – or at least a means of escaping painting, so as to return to it with fresh eyes. In fact, it is as hard to get out of a good drawing as it is out of a good picture, and there was no question of rest, because to do anything requires tension. There is great collusion, I think, between my pictures and my drawings. They follow a different pace, but each is as hard and as painstaking as the other. Sometimes I felt that painting started to appear too much in my drawing – when the drawings became too liquid, too modeled – and immediately I had to stop and start again.

Do you pursue the same preoccupations in drawing as in painting?

I do not “pursue preoccupations.” It’s they that pursue me!

But in either case…

What interests me in drawing, you see, is its austere, its terribly austere side. It has no outward attraction. It’s hard, like salt. Drawing in pen, is, let’s say, sixty times slower in execution than drawing in black pencil. The pen holds you back and the paper almost needs to be incised, like a tattoo – because paper is really vulnerable, it has its “flesh” side. Every time I’ve plunged into it, I’ve wanted to submit the sheet to a shower of poison, but one which in the end would create something beautiful.

Do you sometimes erase them, or to lay in layers, like in the pictures?

No. It is precisely that that’s so terrible in pen-and-ink drawing. Nothing is lost, everything is recorded like a kind of electrocardiogram. And for me the most wonderful thing, of course, it is when the volumes and the whites are formed in a way I could never have imagined.

When you start drawing do you already have an image in your head?

Not. Absolutely not. I’m incapable of imagining a drawing, of feeling it from the outset. I have never known what having an idea in that sense means. Above all, when I work I’m trying to delve into somewhere else, to escape from life. And where I have perhaps succeeded, in the rare times when it happens, it happens like a misfortune, like a brick in a way – splash! Just like that.

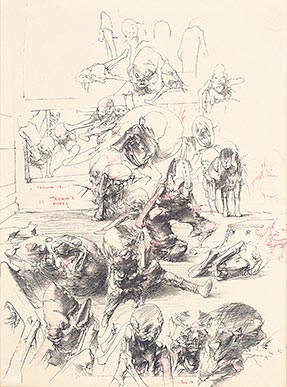

Right: Adam’s Hotel, 1978, India ink, colored ink and pencil on paper, 65 × 49 cm.

So for you art is a means of escape?

It seems to me that any art, not simply mine, is fatally a search for another life. It’s a way of escaping if you want, but what’s dreadful, and above all interesting in art, is that it leads to self-betrayal. One can try to escape and avoid stating the things that torment you, but they always appear.

Art always ends up telling the truth…

Exactly. Like in a kind of delirium. Or confession. And as I can hardly imagine myself going to the priest, the analyst, to those little jerks, and all that. To my way of thinking, the work I do lies parallel to reality. I reckon it’s another reality – it’s terribly pretentious to say so, perhaps. It’s not the reality in which we live, it’s not even my own reality, since the reality in my work becomes larger than mine, which is wretched, like that of all of us. I believe, however, that the drama I live though in my work is no more worthy of interest than the drama of somebody who finds it hard to walk.

Why does this reality include such an obsession with rotting bodies?

Rotting bodies? People have often spoken to me about putrefaction in respect of my work, but I don’t think it’s necessarily that. That’s the superficial, purely anecdotic side, that is. You know, what fascinates me is the extraordinary incalculable complexity of the human body. Because when one looks at a face or a body, one doesn’t only see the flesh side – one sees everything, in fact, even without seeing or touching it. I can well imagine somebody who is in love wanting to touch the nerves, the kidneys, the organs of the other. For me, if you like, the human body is the entire universe, a total and unique world.

But that race of strange figures: where does it come from?

Well, I have no idea.

You have no idea; or you’re not saying?

I don’t dare to…

Is it because you’re superstitious, in the sense that, if you told us, it might disappear?

Let’s say that it’s not my painting or my drawing that frighten me, but the void whence they come. I don’t know what this void is. And I don’t know what it is deliberately, because I don’t want to. In any event this void is all around us, every person, every object is bathed in it.

You don’t like trying to analyze these things?

I loathe analysis. We always end up with the cobbled-together stuff that’s so fashionable today. All analysis appears absurd, inconceivable to me. I for one can only observe certain things when I stumble into them.

There are so many shredded limbs, so much flesh in deliquescence that your interest in them cannot simply be anatomical. Isn’t it instead an obsession with death?

Yes. For me, the real horror is that everything is based on the fact that life, death, the good and the bad all exist. All the bullshit comes from that. I believe that from the very start there exists a universal and permanent debility, even if from time to time there are prodigiously intelligent people…

But are you particularly conscious of the fact of death? People looking at your works often feel ill at ease. At first contact, many feel a shock, even a movement of repulsion.

You reckon? What a compliment! I am being spoiled this morning.

You’ve surely noticed it already.

No. Not really. I cannot know what people feel in front of my work. But, you know, over time I wonder if physical mutilation is worse than things done underhand, than tricks, than humiliation. The physical side is perhaps simply a more spectacular attack. I put everything into my drawing, I absolutely lose control, and that allows me to discover a whole load of things.

You remain however sensitive above all to vulnerability and destruction.

I am just that, vulnerability and destruction. It would be ridiculous to hide it. Artists always resemble their work.

Do the characters you create sometimes relate to other images – photographs, for example – or to people you might have glimpsed somewhere, like all those men with bald pates we saw at La Cupole?

No. On the other hand, tragically or comically, it can happen that when I do a drawing, the figure I’ve just finished walks past the window.

So it seems instead that life imitates art?

Exactly. If a drawing is going well, everything sits for me.

∗

∗ ∗

Right from the beginning, you started doing portraits, I believe.

Yes, when I was kid in my house in Montenegro I drew my father and then my pals, asking them to make faces. That’s how I entered this world of contorted faces. I immediately set out in search of bizarre things. Then, very early on, when I was about seventeen or eighteen, I started doing figures that had nothing conventional about them at all, thereby causing me a whole host of problems at the art school I was attending.

It was already a fantasy world?

Yes. If you like, it was a kind of bad dream that started. And which continues thirty years later.

How was it connected to your life?

Put it this way. My work is a bad dream and my life’s another bad dream. And that sometimes amongst all the confusion there are things that become clearer, luminous moments. But to tell the truth I’ve never be able to separate dream from reality. That’s more or less why I’ve got the painting bug. Why isn’t dream reality; and, why when you’re stopped by the cops, it is a reality?

How do you see your drawing having developed?

It is the writing which has been freed, it’s became more adventurous – if you want me to play the art critic. But it’s the same difficulty of being that always appears. Its that’s a rather big word, perhaps, but I reckon I can’t hide it, it’s obvious there’s something not quite all right.

And that you accept?

If I reject that, I’d have to reject the whole thing. In point of fact, one can’t change one’s life, contrary to all the theories bandied about today.

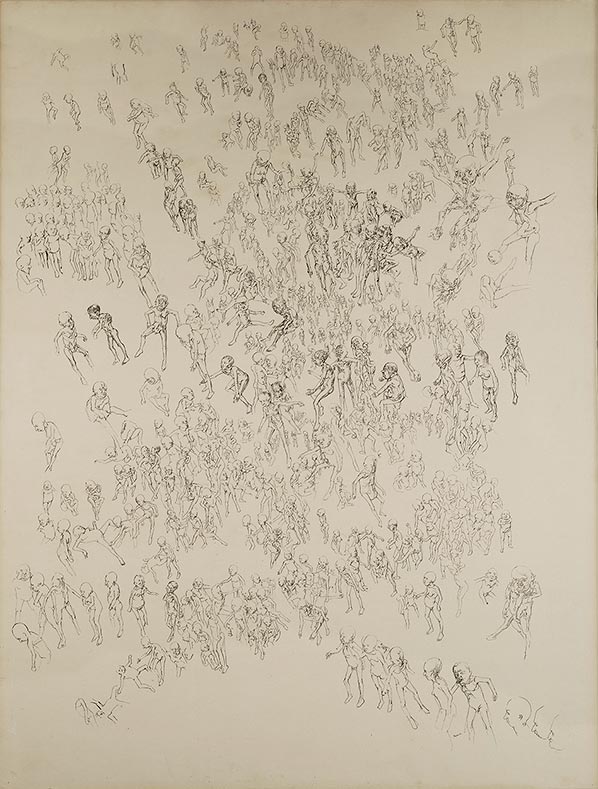

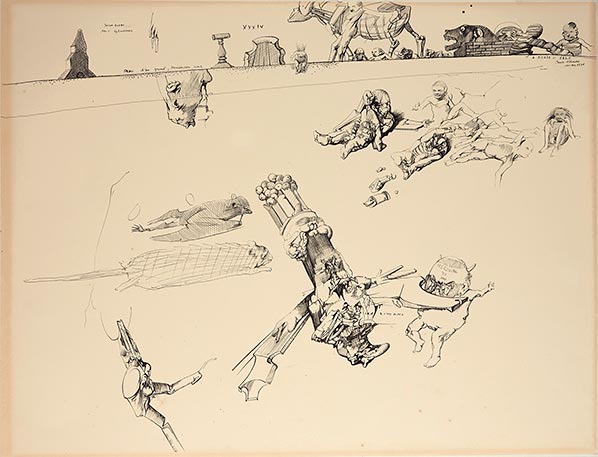

Right: Untitled, 1969, ink on paper, 64 × 50 cm.

Is there a common theme underlying the drawings? I’ve the feeling that some led others.

That’s true. Everything is linked. There’s a single drawing that’s never going to be finished and it leads to the horizon. That’s what excites me, you see. But there’s no real theme.

It’s perhaps exclusively space and the plastic relations that interest you?

Of course. The question doesn’t even arise. I mean, when I am conscious of the purely plastic aspect, I’m on the right path and I’m not redoing something I might have seen in Paris Match or in one of bald skulls in La Cupole, you see?

At what moment do you know you’d better stop working on a drawing?

When I need some cash! No, you know, I never have the impression I’ve finished anything. But there’s always something that happens and that makes me turn them to the wall and start on something else… In the final analysis, I reckon that my imagination, as you call it, is a kind of reality. I think that my drawings contain what Victor Brauner has called “harbingers” – pointers to things that will happen to us.

As one ages?

As only unpleasant things occur in the life most of the time – well, better not to write a handbook on despair, but they say it’ll all come right over time, and they are completely wrong. It’s something nice to say to children, but at eight one’s already understood that time is of no help, quite the contrary, it devours, it destroys!

And this feeling inevitably transpires in your work.

Of course. My work is a kind of private diary – a notebook of a journey on the spot, if you like. It’s a document one hopes isn’t too tedious: what one can call “art”, I believe. That is, having to talk about things without knowing why. And to finish with something of good, it has to be difficult. I can make all kinds of images very easily, but they’re worth nothing. There has to be difficulty and struggle, and these have to be imposed. If not, it’s ready-to-wear stuff, you see. Your drawing or your picture has to turn up like an eruptive disease, without anyone knowing why. There you go. That’s why I can’t analyze it and that one cannot apply to my work any aesthetic or philosophical benchmarks, or anything. One can only submit to it – if one wants to!

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz