Dado sculptor

or

the metamorphoses of refuse

Advance the slideshow manually with the left and right arrow keys on your keyboard. ❧ Hover over the images for captions. ❧ Click on the images to enlarge them (large and extra large sizes).

We reproduce below, practically in its entirety, the text of a lecture delivered by Claude Louis-Combet on October 8, 2014 at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie on the occasion of the publication of Dado, de fer et d’os, in collaboration with Domingo Djuric. Claude Louis-Combet’s text is accompanied here by photographs of sculptures taken in Dado’s studio by Domingo Djuric and Philibert in 1989, by Hervé Duetthe in 1996, and by Philippe Ferrari and Domingo Djuric in 2009 and 2010.

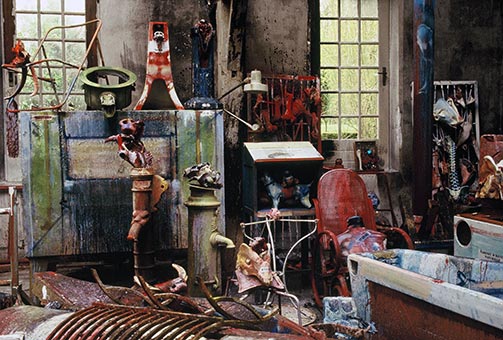

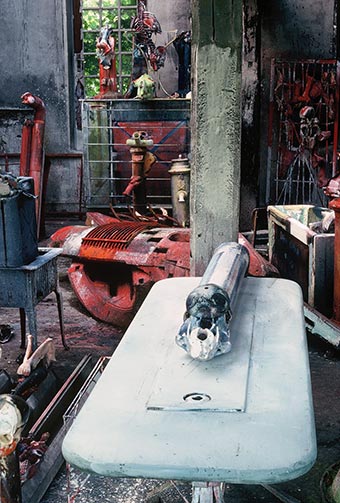

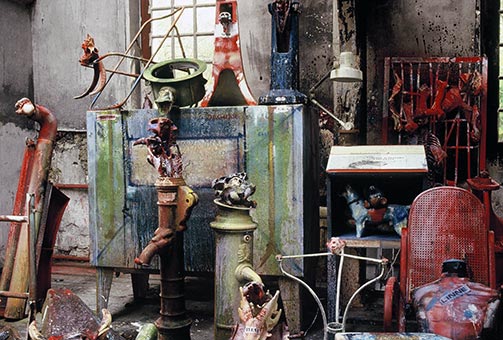

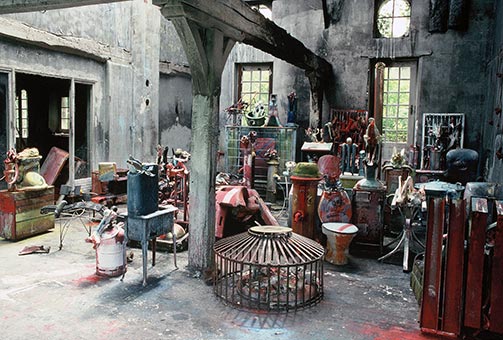

Around 1987 or a little before, it appeared that Dado’s painting had ended up by forcing his hand – as if canvas was no longer enough, as if the illusion of relief conveyed by the figures, their resemblance to sculptures in the round, their volume effects had elicited their invasion of the space outside the picture, the annexation of the objects it contains, the, as it were, colonization of the most miscellaneous things to hand. It marks the expansion of painting, with all its excesses, that nothing can now hold back. The pots of paint and dripping brushes bestrewed over the studio floor at Hérouval lose any reserve they might have had at the prospect of the grandiose conquest of the place and the world by that population of objects monopolizing the space. Once the initial abduction, and, if this is the right term, the rape of the object stumbled upon is complete, then the passion at once to reign imperiously takes root, and never again did the artist lose it.

At this point in time, for Dado, the dump, some treasure in the cellar or the attic, the recycling plant became, both in the imaginative world of his desire and in common-or-garden reality, inexhaustible storehouses, full of rubbish, of things rejected, expelled, abandoned, now offered without stint to his appetite, by which I mean to his creative impulse, to the metamorphosis, to the trans-valuation of forms, and to the dramatization of the inert and the mute.

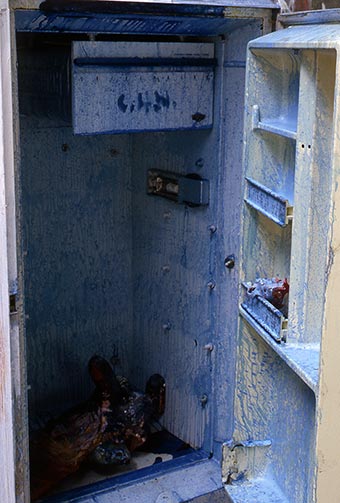

Dado does not operate as a collector. He does not classify, he does not protect, he does not stop at the designated identity of his pickings, his spoils. Deep down within what is a truly demiurgic way of thinking, any salvaged article is liable to become something other than an instrument for its erstwhile use, for its apparent, intended purpose. From the instant when, rejected, ejected, it is divorced from its function, it immediately reasserts itself through an ability to become something quite different, all the while preserving, in its outward appearance, hints of its initial, utilitarian function. Thus, with a washing-machine or a piece of pump housing enthroned in Dado’s imaginary kingdom, one is reminded of what they used to be long before. Now extrapolated, they acquire, thanks to their place in this most unsophisticated of settings, a symbolic status one might never have dreamt for them, but which languished, latent in the fundamental morphology of their materials: rotund, open, full, and overflowing with detritus redolent of humanity and childhood, the washing-machine starts to look like a maternal entity, while the piece of pump housing flaunts its outlet like a vestigial penis, a flagrant allusion to virility.

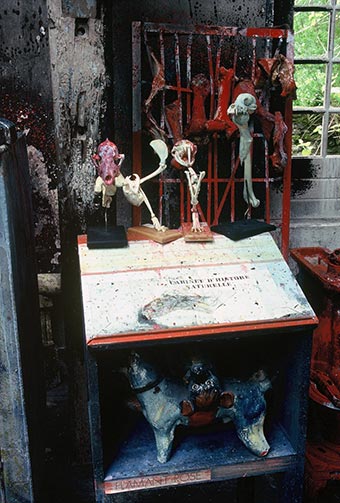

Thousands of disparate things, damaged, obsolete, unusable, have passed through the workshop, and some lingered on. Every single one is special by dint of a strange quality of presence, through a symbolic and intentional power of suggestion, be it alone or in conjunction with the others. In Dado’s hands, every object extracted from the hole or heap of refuse comes back to life, gathering round it its share of insolent, comical, or pathetic oddness, as well as an expressive power that propels it up the ladder of artistic creation. Every single one of these hand-me-downs signifies something, has some message to transmit, some reminiscence of the human condition to unveil before our eyes, violently, without compromise or pity, but not without humour and affability. At first glance, faced with a mob that seems almost to howl in its dumbness, grimacing and gesticulating in its inertia, face to face with this sorry shambles of things that conspire together within a space without horizon, without exit, visitors can be gripped by angst or disgust – since there is too much din in this silence, too much agitation in this immobility, too much hostility in this peaceful country haven, out among the wooded foothills of Hérouval. But, after the initial shock, if one lets one’s eye wander over what’s there, if one walks round from group to group in the decoction of urban sprawl represented by the workshop, those with a proclivity for strong aesthetic sensations will be struck by all these ingenious coincidences, these assemblages of objects, by the prevailing atmosphere of uncontrolled, monstrous, cackling, unbridled farce, closer surely to Rabelais or Hieronymus Bosch than to Dante or Sade. The bloodstained wash that soils such a large number of rooms, the arrangements of bones, of bandages, of butcher’s hooks, and beds of pain – such an evocation of mass grave or torture chamber, this anteroom to Hell is promptly contradicted or counterbalanced by the broad humour of kitchen utensils, of things domestic and hygienic, of tuneless pipes. The atmosphere is heavy and dark, and it arouses suffering. But at any moment laughter can erupt, even where one might have expected rather a scream.

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Photo: Konstantinos Thomopoulos.

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Photo: Konstantinos Thomopoulos.

Right: Pline Chair, 1989, assembly of painted objects, 83 × 55 × 45 cm.

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-Cci, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Photo: Konstantinos Thomopoulos.

These painted objects can be considered separately, each in itself, like so many avatars of provisional, transitory, transmutable sculptures. But they acquire their full meaning and power from their permutation, from their promiscuity, from being arranged in combination. Together they form a world, but a world that has reverted to chaos following all the disasters of history and the corruption of the species. Or rather, they are incorporated into the materialized spectacle of one single, enormous nightmare. They compose a surging, disturbing, dubious, motley crew, and the studio in Hérouval imposes itself on our vision like some figment of a den of thieves. It is all very well telling oneself that everything here is dead, an air of life circulates within due to the connivance and complicity between all these objects, composing a ghastly impression of humanity. Even the animal bones are set up in a display reminiscent of human models that speak of cruelty, of voracity, of impulses left unsatisfied. Or else, these beasts have perished, crushed, desiccated, bestrewing about themselves the testimony of their torture: cats, rats, toads, whose bodies seem to condense within them the power of suffering life itself. For Dado, and for us who follow after him, these are surely infinitely fraternal beings summoned to stare at us from the other side of the looking-glass and to remind us how small we are, and who reap nothing but horror. For there is something of the moralist and the pessimist throughout Dado’s oeuvre, in which monstrous figures emerging straight from the obscurity of being and time make materially present the darker side of humanity – the shameful and ineffable something humankind bears within it. A metaphysics of the grotesque: such is the lesson of truth that emerges, intuitively, from Dado’s work, in all its modes of expression. The playful air of certain scenes never quite obscures the deeper vision, the pitch-black, terrible, and desolate vision of the wretchedness of human existence.

The sculptor named Dado has chosen to transform beings from the scrapyard – that is to say, things rejected and abandoned back in the netherworld of the refuse dump. When he salvages them, when he completes on them his operations of disfiguration, of transfiguration, of metamorphosis, it is as if the object, once useful and familiar, suddenly constitutes no more than an outline, a potentiality, an interpretation – what the philosophical tradition since Aristotle designates as matter. Matter is not neutral; it still bears within it an initial form, but uncoupled from its function and now embodied as a constellation of suggestions. In an armchair, a stove, a radiator, a urinal, or a painting stretcher, Dado perceives something like the resonance of a will to be – to be again, elsewhere and otherwise. For the artist, in this instantly established encounter or recognition, the thing’s desire equates to his own. With his eyes, his hands, with his body, no less than with his mind, he harkens to the unspoken language of the entrapped form. It is like an appeal, if not quite a supplication, but no less poignant. And, since, from time immemorial, the artist – Dado – has dreamed long and hard, it is from the obscurity of his dreams that he garners his response to the dense expectation of the object, condensed in its muteness, its passivity, its accessibility. Often the creative act is on the face of it limited to very little: a few dashes of paint, reddish, greenish, yellowish; the juxtaposition of some objects; the strange promiscuity of an installation, and, what do you know! the theatre of the world and of humanity is set in train in the protective space of his studio cum caravanserai. The workshop as material shelter, as a binder of permanent gestation, as an island reserve for mutant species, threatening yet threatened. It is imagination that holds sway here: inexhaustible fecundity, ingenuity, proliferation. The fire in 1988 did not stem the galloping expansion of objects and forms. On the contrary. The very next day, amidst the smoking ruins, Dado of Hell resumed his work, as if the fire had merely pointed out to him some new paths, afforded him fresh creative suggestions, compelling him, in an inner need, to give meaning to the destruction, to the consummation. What remained after the flames had done their work lives again, in the exaltation of the traces of combustion and in the exhibition of its scars. The cycle of death and resurrection kicks in once again and his demiurgic will remain intact. And it continued undimmed until the end, until his last breath. The great projects at Orpellières, in the Saint-Lazare chapel at Gisors, the blockhouse on the coast at Fécamp testify to the creative vitality of an artist goaded into frenzy, into the transgression of every limit, unto death.

There was something playful about Dado. Deep down, the visionary, the prophet of evil times, the familiar of monsters and monstrosities, cultivated the spirit of childhood, a kind of innocence that made a mockery of calculations and strategies. With its ability to absolve every cruelty, every turpitude, this vein of freshness manifested itself particularly in the assemblies of mobile sculptures made of spare parts, of odds and ends, which, if moved or if their components were swapped, showed themselves capable of transformation. It is the lightness inherent in transitory things that breathes his spirit into the work […].

In this demiurgic en-terprise of salvaging and transmuting refuse, Dado brings out what already lay latent, like an invocation, within his painting: the shift up to the third dimension and the autonomy of the object in its occupation of space. But this is not all. The arrangements, the settings of the objects, their interrelations allow one to perceive that they have also accumulated a fourth dimension: that of interiority. This surely puts them on a par with the painted figures displayed in two dimensions in Dado’s pictures: they end up as bearers of intention, generally of a dangerous and harmful nature, and representative of an all-conquering, irrevocable, and pathetic fate. This is why Dado’s oeuvre appears so profoundly embodied – a far cry from conceptual art, and part instead of a great expressionist tradition that can be traced back to the sculptors of diabolic figures in Romanesque churches.

Thus, for Dado, the passage to sculpture, even in its most ludic guise, is not at all a diversion designed to channel the artist’s enormous creative tension distilled in his great paintings. In Dado’s oeuvre, sculpture represents a path, a domain of completeness that enabled him to express, with all the authority of his genius, yet with greater freedom, his torments, his obsessions, his avowals of bitterness, his deepest questionings. The ephemeral, sometimes fortuitous, and certainly particularly perishable character of the painted objects and the occasional installations vouchsafes to this aspect of Dado’s output the indisputable truth of something that touches and that hurts when its touches, as well as of something that elicits laughter or conjures up dreams within the sanctuary of great art.

Claude Louis-Combet

20th August 2014

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz