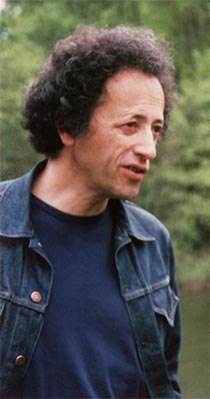

Dado by Bernard Noël

Two texts by Bernard Noël. The second text, The Multiplier, is taken from the catalog published on the occasion of the exhibition of drawings by Dado at the Isy Brachot Galerie (Paris) from November 16, 1978 to January 6, 1979.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

The word came back to me just as I was recalling the time François took me to the first Dado exhibition at Jeanne-Bucher’s, in 1971. No other exhibition has ever had such an effect on me: my vision, though violently occupied, suddenly receded, repelled by an internal invasion analogous to vertigo.

The gallery space was contaminated by the energy radiated by the pictures, and it was all blue. A blue intermixed with a white dust so penetrating that it powdered inside the body, bringing in its wake the theater in the painted scene.

Usually, one takes up one’s stance before a canvas and this face-to-face encounter unfolds in accordance with the attraction exerted by the thing painted. The respective places are fixed once and for all whether the beholder paints or not. This time, things went off very differently because the painting overflowed. François had warned me: “Hold on tight!” And he had made sure we would visit in the morning, when the gallery would be by all accounts empty.

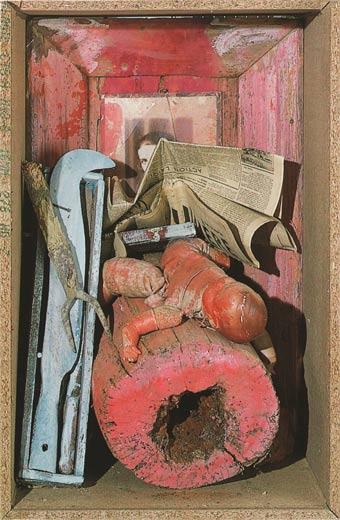

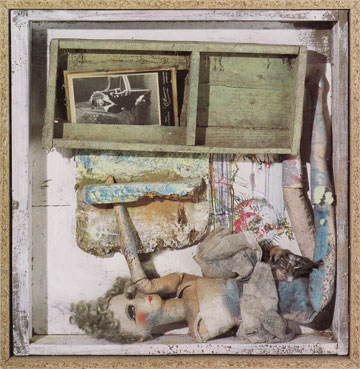

73,5 × 48 × 40,5 cm.

Dado’s imagery dazzles one as much by its originality as by its fury. In its projection of the unbearable, it practically bursts the eyeballs, and yet, once one confronts it, all this withdraws into another explosive condensation: a kind of gathering storm whose energy courses through the viewer as the eye sweeps the surface. But if one remains merely fascinated by the image, one misses its essence – the swirl of energy that infuses the figures and their arrangement. The violence it illustrates releases this surge of energy but it also ensures the synthesis between the act of representation and the precipitation that transforms viewing the image into a wholly physical experience.

In fact, Dado exacerbates that paradox in figurative painting whereby the heightened expressivity of an image accelerates it to the point of evaporation. Thus, he places before us figures whose postures are so extreme that they verge on caricature, simultaneously conveying the twist ripping through life.

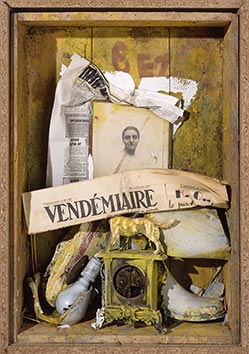

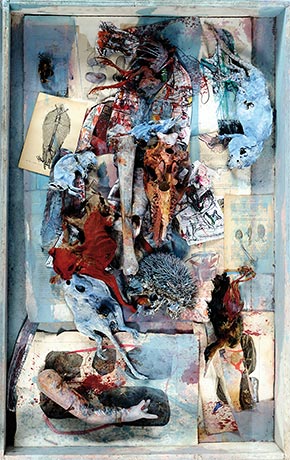

70,5 × 49 × 20,5 cm.

Dado is known for creating monsters – and thus hybrids! His oeuvre is commonly described as a factory turning out haggard, bestial creatures.

This is at once true and false: true if one keeps to the surface of the image; false if one delves deeper and examines its constituent parts. Still, this accumulation of monsters must fulfill some need.

Great painters always renew their work within a continuity. It is clear that Dado strives neither to shock nor to surprise, because such an aim would in the long term become systematic and in consequence superficial. Something else is inevitably afoot. At least at a primary level, this surely has to do with the atrocities of our time, but, even within in these limits, the horizon would lack symbolic power.

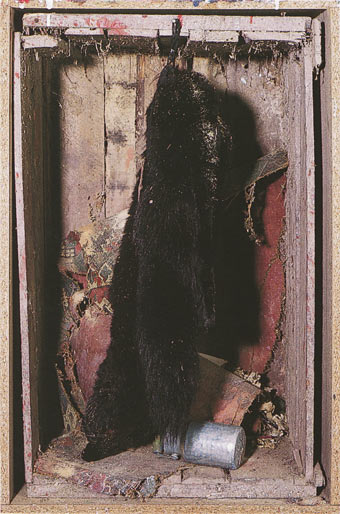

82,5 × 53,5 × 46,5 cm.

The common denominator then is not verisimilitude; it resides instead in a commonality of materials that one hesitates to call by its name because that name is “meat.” A pictorial meat, sometimes, as when it thickens, stains, or sprouts, equating to flesh; at others airy, as when it emanates an elemental space in which all can breathe. This multifaceted “meat” is painting. More exactly it is Dado’s painting, because it is meaty and not aesthetic.

The image does not just depict the maimed, the carnal, the breathless – it contains them, they are conveyed through impression rather than by vision. The difference is a capital one since, before such an oeuvre, the eye is initially drawn in only insofar as it is one of our senses, and, as such, is able to trigger an act of physical participation. It is not enough to talk about emotion, because in fact the work concerns the entire body, a body positioned in such way as to receive the full force off the painting, morphed into an organic impulse. To that purpose, and after it is interiorized, the view of the picture gears up into an internal event, even at the cost of some violent outburst. We are at a far remove from those paltry decorative or retinal excitations championed by institutions today.

85,5 × 57 × 11 cm.

One notes in the evolution of Dado’s work how the image withdraws, apparently causing him to employ more crudely meaty materials. His collages, for example, are combines of waste from the studio treated as anatomical fragments that are assembled to the point of incarnation. It looks as if he rebuilt their limbs “in the flesh”. The astonishing thing is how “clean” painting that sought excess in the violence of perfection is thus succeeded by “dirty” painting that accumulates stains, blemishes, and scuffs, opting for graffiti over the figure. The sullied and the raw congeal to create an impression of organic violence to convey a sensation of engaging with the thing in itself.

The groundwork for this change in direction came in the 1990s, with boxes and sculptures, assemblages of heteroclite objects – bits of wood, cans, skulls, mummified cats and foxes, bones, shoes, cauldrons, radiators, etc., – morphed into visions of rendering or dissection. But well before, there had already been collections of bones drawn over in pen, as well as the famous car bristling with bones entitled Front-Wheel Drive.

Ceaselessly, Dado works away, analyzing the image; it might be said that today he distills from it so as to come forth as he really is. In other words, gesture, having once transited through figures, now turns to flesh, embodied in forlorn materials given form by its own imprint.

Hybridization, then, does not merely spawn monsters; it is secreted in a heartrending act which, at the cost of a certain amount of effort, consists in splicing our temporal existence with gestures that create a “work.” Thus does all creation harbor something monstrous because it adulterates energy earmarked to serve the species by hijacking it for an individual purpose. Limited to the intellectual realm, this fact remains unseen; but once an artist sets the scene for the anatomical theater that underpins it, violence bursts out. Dado’s art attains that physical dislocation which lies behind all creativity in his themes, materials, and colors. It is the vertiginous nature of this work from the life that ferments its capacity to unsettle us physically.

∗

∗ ∗

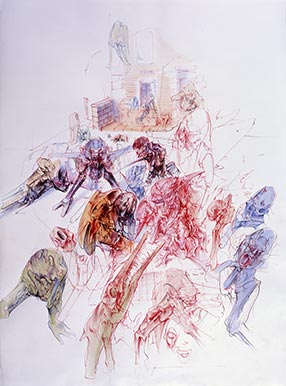

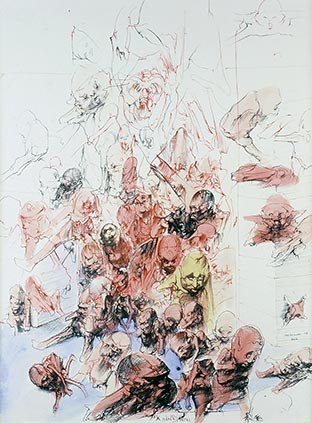

The Multiplier

Here then are drawings in which something rather monstrous extends, proliferates. This can be deciphered: faces, grimaces, beaks, bones, teeth, genitals, eye-sockets, mouths, beak-noses, but the sheer accumulation hurls forward the eye as it reads, producing a quavering in which all these details lose their names, their referents: the elements, benchmarks of meaning, are scrambled, and the impression gains the upper hand.

Thus, the disturbing thing about Dado’s drawings is less what they show than their manner of exacerbating the depiction by juxtaposing the contradictory means of both fragmentation and dynamic unity. Initial effect: one forgets to identify what is clearly represented, and the scene changes: no anecdotes, just action. A misfortune. And always from life, on the wing. By accumulating details, Dado sets up a velocity that obliterates the detailed, because it renders the whole significant. The seething only seethes to accelerate a formation through which it gains order and impacts en masse. This impact beggars description, halts the reading: could it be that what it is made of is less important than knowing what it is?

But what it is, although not reducible to the elements comprising it, is not distinct from them: this is Dado’s coup de force, in the art known as figurative: to constantly duplicate what is figured by multiplying it. This movement of multiplication, instead of highlights the figurative, empties it to make room for itself; only the effect it produces resembles the one each of its components might elicit. It follows that, if all the fragments are charged, their overall load is infinitely larger than the sum of their parts: it resides in excess.

Right: Untitled, 1978, ink and watercolor on paper, 77 × 57 cm. Courtesy Archives Brachot.

This excess, however, operates at the level of the readable, – if you will! – in all zones of the drawing, but each just offers purchase, where the stampede can begin anew. Thus it is seen that the series of effects (speed, shock, excess) are established solely so as to compete with another series: the details, elements, fragments, whose contradictory situation is necessary. And the consequence of this state of tension is that the least part of it forms one with the unit, whence arises for the viewer an ever-present desire for all this body.

In this manner the upheaval in the visual space is total: from the surface of the drawing to the eye it is no longer just information, just knowledge that circulates, but this desire that wants to see more. The eye can also decipher each individual fragment, understand that this face is a cry, this other a graze, yet another, a disfigurement. Yet this too is to fall short: the eye generalizes; but then comes an outburst that teaches it nothing, that urges it to be excessive.

Why? Perhaps because their immobility is that impossible state to which we aspire – an always which defies the wind of death, which is also their wind. Immediacy is not a place; it is hovering on a shifting perimeter where we are present – nothing other than present. In the flash of this presence, our glance and relationship are free of all censure: they are physical, uniquely. Into this, Dado projects us, in visions, and his dance macabre is then a festival of searing life.

Bernard Noël

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz