Dado by Gaëtan Picon

This text by Gaëtan Picon initially appeared in the catalog to the Dado exhibition held at the Galerie Jeanne Bucher (Paris) from March 30 to May 8, 1971.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

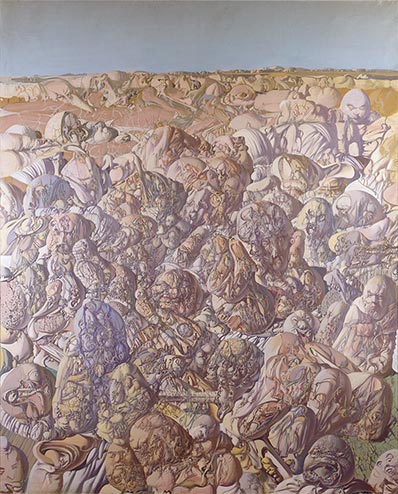

Photo: Domingo Djuric.

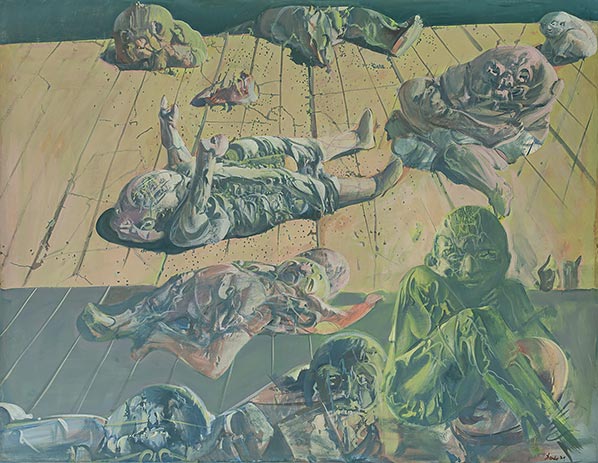

Duško Vujošević Collection. Photo: Vladimir Popović.

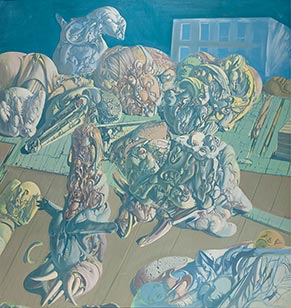

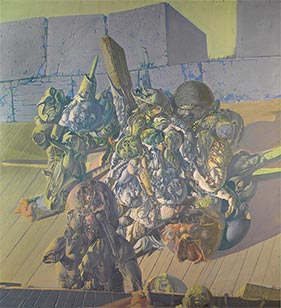

Does the light come from this blue sky that narrowly borders the wall or the raft at the very instant it piles into in the heart of the earth, which – as here, in Flanders, in a splendid piece of painterly bravado – takes up more than half the canvas? In the absence of the sky, it remains the same: the light from an aquarium, perhaps, where water, long-vanished, has left the traces of clarity. As for the time of day: bluish dawn or pinkish twilight? We scarcely know, and it’s better to say that there is no hour, at least in the sense that our days have them; but it is not certain either that there exists a point in time, since we hesitate between the term “apocalypse” (the year two thousand is not far off), to which testify these mangled, churned up bodies, worn out to their sinews, and limbs that suggest in particular – thrown together into this prehistoric teratology – chubby-cheeked children condemned, by elephantiasis, never to live. It is unbecoming of us to enter – stealthily – into someone else’s dream; and if, on closing one’s eyes, the image persists, it has perhaps disappeared from the canvas so impalpable it appears to us, a phantasmagoria projected on an empty screen by an invisible magic lantern, a tide covering its space in a unique and irresistible movement; its inextricable imperative defies us to identify from what assembly, from what calculated act on the part of the artist each image derives its distinctiveness. (Consequently, how can one risk having a preference or describing an advance?).

Nevertheless, the image is still there, deployed far-off and with ostentation – the decorative unity of a great fresco, a baroque ceiling – and attesting, if we move a bit closer, to the fact it is a painted image, every detail keeping to its place, or to the margin, in perfect complicity with the whole: this dream is clearly that of the painter’s hand, constantly more evident and assured. As for this world whose objects and successive appearances we now hesitate to name, the least we can say, at first glance is that its foundations are rooted in violence and death, in the sound and the fury, in which we feel permitted to decode at once the contents of a personal destiny marked very early on by encounters of this type, and the signs of a period. But we perceive it through a filter, hazy: tapestry, toile de Jouy, vignettes lifted from some old book, folding-screens for children’s rooms or dreams, tales in pink and blue, wonderlands of a patient, sly gentleness, by a tender heart that cannot endure violence, and repudiates it, not by consigning it to oblivion, but by transforming it into imagery. The wound, however, does not close up: and a further glance reopens the scar. – Decidedly, words serve for naught. One should never stop looking.

Gaëtan Picon

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz

Right: Casque obligatoire, 1970, oil on canvas, 210 × 188 cm. Collection abbaye d’Auberive.