Dado by Georges Limbour

This text by Georges Limbour comes from the catalog to the Dado show at the Galerie Daniel Cordier, Frankfurt, in 1960.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

Turning off the great highways of contemporary painting, in marginal and uncharted regions of art, where the destinies of strange and beguiling creators unfold, Dado’s painting offers its own peculiar enigmas. Clearly oblivious to aesthetic preoccupations (and sometimes even, as profound painters’ works can be, visually unprepossessing), the imperative and immediate projection of obsessive dreams, with the disconcerting absurdities through which the subterfuges of the unconscious appear, this youthful oeuvre strikes the viewer by its assurance, and by what one might term its dexterity, the hand acquiring all its skill from the intensity of the vision.

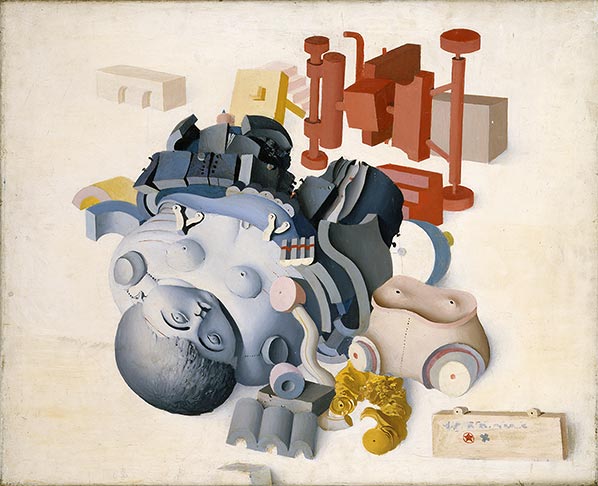

Strangely, Dado’s enigmatic world that our bemused reason tries to decode is, like Limbo, occupied by neither death, nor life. The figures, although monstrously adult and perhaps prematurely ageing, cling on to remnants of the innocence of childhood. Occasionally genuine children leap out of the painting, beaming with health and chubby-cheeked. We are assailed by legions of babies of dubious age, rotund and pink, of authentic or abused innocence, with purity intact or violated. On what terrible world do these dolls’ porcelain blue eyes stare out? Some childhood obsession? A picture from about two years ago shows us an untidy paradise, under threat, perhaps from the innumerable toys.

A world then of fresh flesh and hospitalized bodies; juxtaposing, perhaps, blossoming lives and, already, misfortune and destruction.

What strikes us most in this bright, clear painting, like the smooth coat round a sugar-almond, and whose first colors (others will appear thereafter) are pinks and pale blues, insipid colors that rock the two wailing sexes of this little humanity, is the way the surface fissures, not through some natural, material desiccation of the substance, but by dint of the artifice of a perversely skillful brush that delights in crazing any surface presented to it – from living flesh to material objects. Every ingredient in Dado’s world – the before-term babies, the premature old men, the stones – everything cracks. If there are walls or monuments, they crumble, falling into ruin. Moreover, many of these pink, reddish or sometimes off-white creatures appear to be made out of terracotta or dried clay, on the point of splitting or bursting. They suffer from a fatal thirst in a land deserted by water, devastated by desiccation.

From shattered innocence to a desiccated, monstrously rimose adulthood. we remain uncertain as to the direction of the flow of time, for sometimes it appears that the parched clay the solidified creatures or the exploded stones in the landscape are already drinking in the muggy air perhaps presaging rain and that (if they are not on the contrary the dilapidated remnants of an age long-past), plants are already sprouting in cracks in the human flesh and in slits in the stones – lichens and moss, all naturally of the family of succulents and resistant to drought. Even flowers grow; acidulous ones, true. And then on the branches, birds. Are these surviving stragglers about to leave this world? Or, on the contrary, are they harbingers about to take over? But if the rain (a lustral dousing, not some commonplace chemical element), if the blessed rain were ever to arrive, should one not be afraid that it promises some other, unforeseeable evil?

Georges Limbour

Paris, November 1960

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz