Dado, Beyond Narration

This text by Françoise Choay initially appeared in May 1971 in number 102 of the journal Cimaise.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

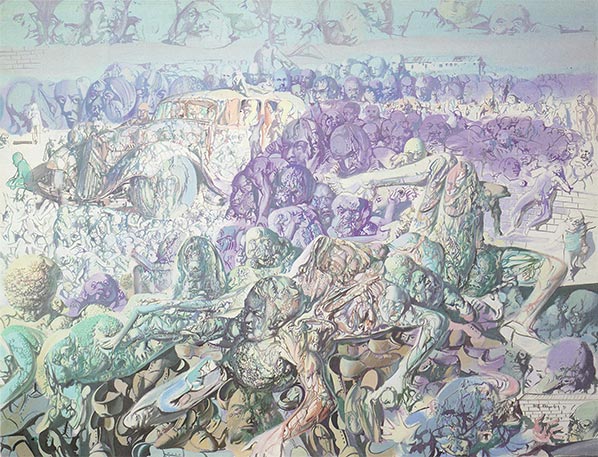

Since 1960, the year when he painted the decisive Thomas More – petrified and bloated, marked by the thousand wrinkles of a destructive malady – Dado has traced his course in the field of painting, straight ahead, without letting anything stop him or deflect him. Untouched by Pop, new realism, optical or conceptual art, he continued his solitary way, dreaming at first, producing numberless drawings like a production of nature, a universe in which the various kingdoms were confused, a world at once vegetable, animal and petrified.

This isolation has caused Dado to be situated “at the limit,” in the tradition and the line of a fantastic art said to be eternal, a sort of pictorial folklore of the depths. Bearing the same label, according to some, as the visions of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel; but such a comparison is allowing oneself to be trapped by surface similarities: the teratology and the strange, and the neat cleanness of the cruel, without giving a thought to the meaning of the picture: its space and its order.

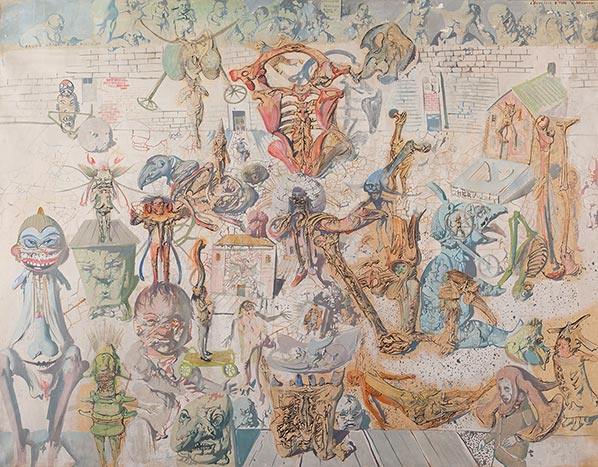

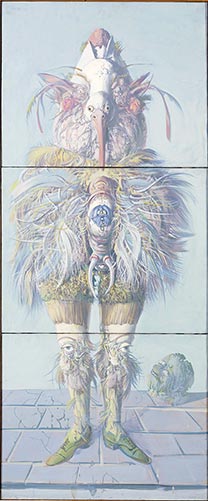

Even more, Dado has been classified among those narrators whose reassuring activity is today relegated by the avant-garde to a constellation of knowledge with which it has itself broken. And in fact these mineralized or feathered monsters, these foetuses with the contours of vegetables, all this people which squirms in the fissured landscapes where we identify without difficulty the surroundings of the painter, are they not caught up in common history? The Hospital of Gisors, the walls of Vexin, the farms, the rats and the flowers of Herouval, like the Breton strand discovered in 1969, are they not the explicit reference and the very condition of the narrative?

It is something else again. This painting, which is believed to picture so well, in reality pictures nothing, tells nothing, represents nothing. Perhaps this is because it presents. It presents the unknown, that which has not yet been verbalized, that which has not yet been organized or centered. It opens itself to the inscription of a cruel universe where the gods are absent and the heroes crumbling. And that is exactly what differentiates and cuts off without remedy Dado from the visionaries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. His painting is no longer linked to a textual reference, it no longer recites the hells of theocentric tradition nor the phantasms of a triumphant anthropocentrism; in it man is no longer ailing, ridiculous or absurd, he is pulverized, reduced to a growth, to dust, wiped out and effaced by a great cataclysm.

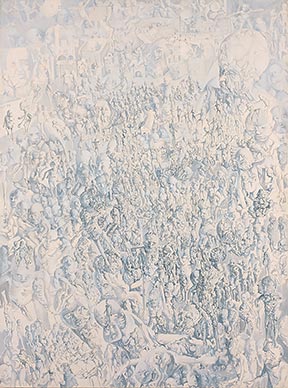

Thus, in contrast with appearances, Dado’s painting is to the highest degree in step with current reflection. It has inserted itself by its own means, admittedly paradoxical, in the great balance of representation. And if we take a bit of trouble to study it closely, we may, from its beginnings, situate the work of Dado in the double tradition of demolition and trace. Demolition which is, in the first place metaphysical, which begins by being the very subject of paintings still constructed according to the logic of the subject and representation, such as The Cyclist done in 1955, with a bent-over robot who is losing his pieces and his bolts. A demolition which, little by little, disfigures itself to “take place,” present itself, according to a progression which leads from The Architect (the title itself is meaningful) of 1959, all fissured in his wheelchair, to the crumbling structures (gutted houses, walls in ruins, broken up tracks) and to the more rocky than petrified flesh of the humanoid monsters and vegetables. Painting of trace as well, we said, and which is straight away manifested in the dialectics of effacement, in the play of acute graphism and tender colors.

Episodical, but constant since Dado’s beginnings, these happy moments of abandonment, those in which Dado brushes up against surrealism, are extremely interesting, because they cast light upon the way the work is produced by showing its other face (that against which it is affirmed), because they aid in the seizure of the ambiguousness and the vertiginous point in which it is inscribed. Also, because they permit a better measuring of the difficulties of Dado’s approach and the difference of his work in the great movement which attempts to liberate painting from the subject, from man, and from a verbal text. Is it not both more perilous (since he must defend himself without let-up against traditional images which illustrate and represent) and more effective than any ironical power, to cause the emergence of an initiat-ing imaginary quantity than to condemn oneself to pure asceticism, to the poverty of poor signs which, finally, call forth new speeches and new literature?

The last exhibition of Dado seems to be a landmark in the painter’s conquest of his purpose and his historicity. Historicity which consists, paradoxically, of delivering this painting of an infra-historical world, the world of the mineral, the vegetable, the failures of nature and the proliferations of the unconscious, against which humans try to reassemble.

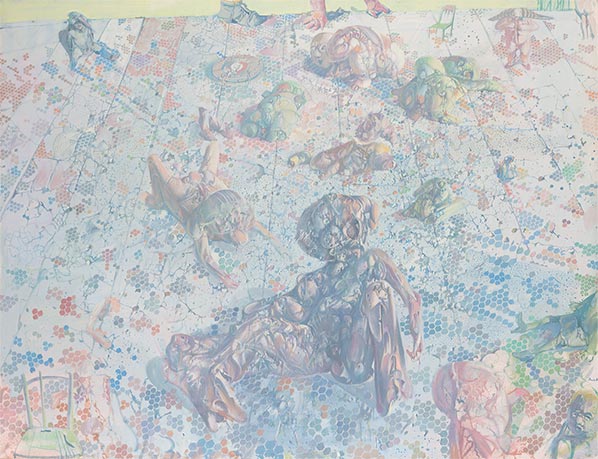

The monsters which, from the epoch of the first foetal babies, and through multiple avatars, have been in Dado one of the operating means of his presenta-tion, the monsters have rediscovered their massive and global, precise and indistinct, presence, a moment abandoned to the epoch of the beaches strewn with solitary beings, in which the painters aim seemed to be dominated by a spatial problem: that of finding an order of presentation which was neither that of classical perspective nor that of the naive juxtaposition of forms without illusion of depth, nor that of the suppression of voids (all organizations exausted by Dado). In 1969, at the moment of the beaches, Dado tried a superposition of planes, parallel to the bottom of the picture, the last band being occupied by the sky. There is no doubt that this series of cuts constituted a stage in his actual evolution, which has integrated in a magistral fashion the geometry lesson. Dado’s invention is a sort of vast sloping plane which constitutes a means of reversed perspective (breaking out toward the spectator) and henceforth serves as a stage or a floor for the painting. This platform, or tiled surface, or passage-way (constructed and graduated) seems to serve a double purpose: that of involving the reader more directly, in short of threatening him, in a slide which carries along and orients the presentation toward him, and by disinvolving the painter, on the contrary, more completely as far as subjectivity is concerned. For this scene-setting and this counter-perspective permit him to take a new distance with respect to his picture.

And on the dangerous soil which simultaneously welcomes prints and rubs them out by crumbling away, the familiar, daily object, minutely described and represented, which – buildings, furniture, clothing – always has its place in the work of Dado, finally takes on its full value and its sense. The why of the café-tobacconist’s of Gisors of a dog house or an old overshoe, seize us at last with force, in a canvas like The Children’s Room, where two dilapidated little chairs are the illusion, the clue in representation, to a world which is neither a frame, nor a setting, but a fragment already in fragments.

This canvas, The Children’s Room, is a strange picture. More accomplished still, perhaps, than the Réveillon (where the role of the chairs is played by bottles) or Menage (Housekeeping), more baroque with its bucket, its brush and its tin can. The Children’s Room is beyond a doubt a picture-landmark, as in former times, Thomas More, which permits measuring the distance already run: presentation freed from the habits of looking, lodged finally in a structure of space which is particular to it; a freer demolition of the metaphor; a representation more completely integrated into that which denies it.

Thus Dado has known how to break the antique enclosure which imprisons the painter and is, for that very reason, situated at the point of contemporary art. Beyond the deceiving evidence of his monsters and the seductions of his palette, this work – one of the most important of the present time – remains also one of the most difficult. A cruel presentation – teratology and cataclysms – but nevertheless serene because of the absence of the painting “I,” it seems that the reversed setting by Dado has taken as its precept the very one of Arthaud with respect to the theater of cruelty. He said, “Theater should equal life, not individual life, nor of that individual aspect of life in which CHARACTERS triumph, but a sort of liberated life, which sweeps away human individuality and in which man is nothing more than a reflection.”

Françoise Choay