Dado by Philippe Dagen

Spectres in the Stone

Extracts from a text by Philippe Dagen written for the catalogue of the exhibition “Dado. Collection Daniel Cordier”, at the Galerie Chave in 2004.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

One runs […] no great risk in affirming that the works reappearing today in this exhibition, more than forty years after their execution and their first presentation to the public may well surprise the eye […]. If they had become hackneyed not long ago, words such as “stupor” and “revelation” might come naturally to mind.

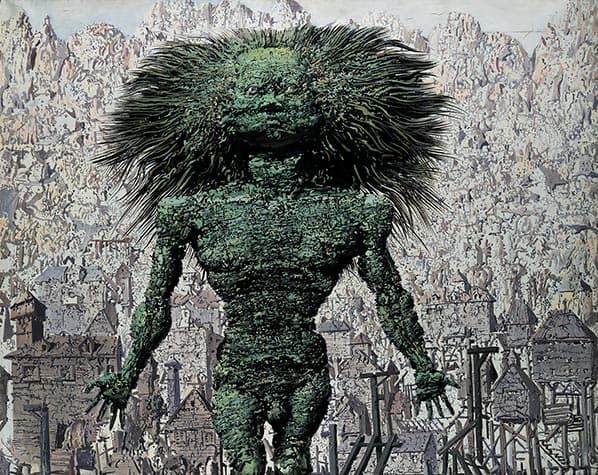

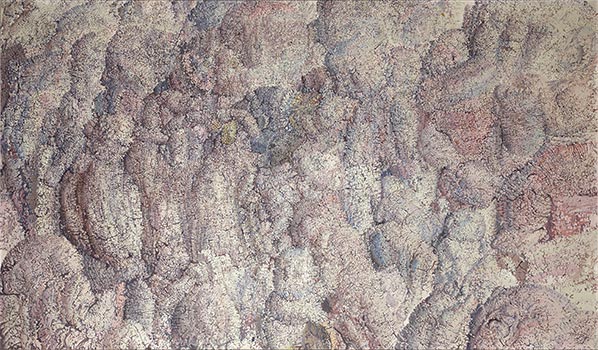

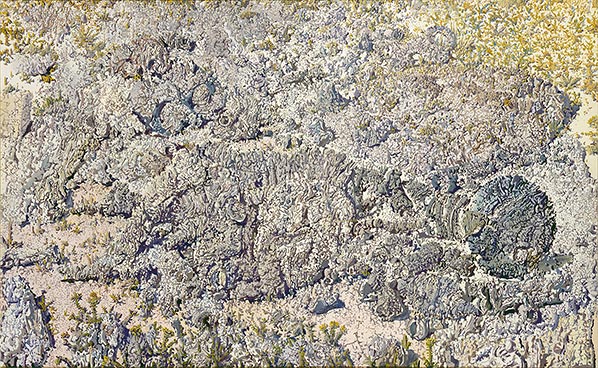

[…] [F]ragmentation, dispersion, dissolution are the principles [behind these paintings]. At first glance one makes out small, separate forms, some notched, others more compact, which seem to cover a lighter coloured surface. They are innumerable. Finding a word to describe them is no easy task: one might call them coral or stones, or petrified vestiges, concretions. If a hint of green might indicate vegetation, it is the mineral that reigns supreme over these expanses of desert. The sky itself, when a sky distinct from the ground does appear, is invaded by clouds so dense that what is aerial can scarcely be separated from what is terrestrial. It might be sand and dust below, with cliffs and agates above: a world without wind, water, movement – almost without life.

Close up, the eye observes a proliferation of serried, close-knit daubs of colour laid in with method. The painter seems to have sought to mislead our vision by presenting impeccably meticulous depictions things usually considered unworthy of representation – stone or dust. Standing back, the eye discovers something else: relatively clear indications of what are one or several relatively obviously human bodies.

[…] [In these canvases] the figures encrypted appear at various levels of legibility, from the almost imperceptible to the indubitably present, from a scattered skeleton to the more or less complete, though deformed, body. Figures lurk everywhere: in the walls, in the grass, among the stones, the trees, the clouds. A painter has simply to pass by and pay them attention, and the whole ghostly world cuts free from the matter in which it was locked up.

Forty years ago, that painter was called Dado.

Philippe Dagen

May 2004

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz