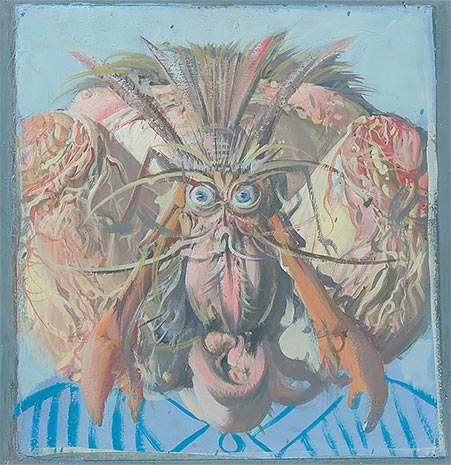

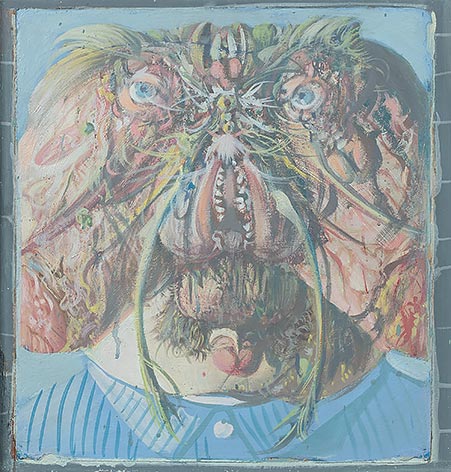

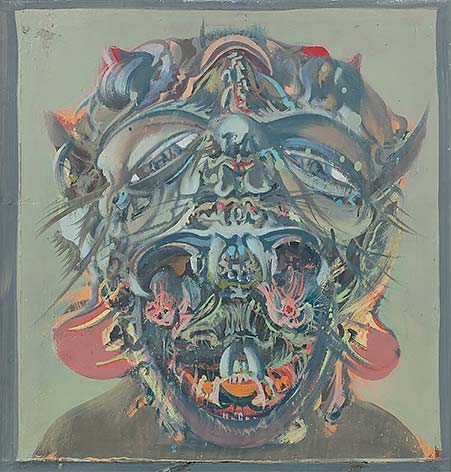

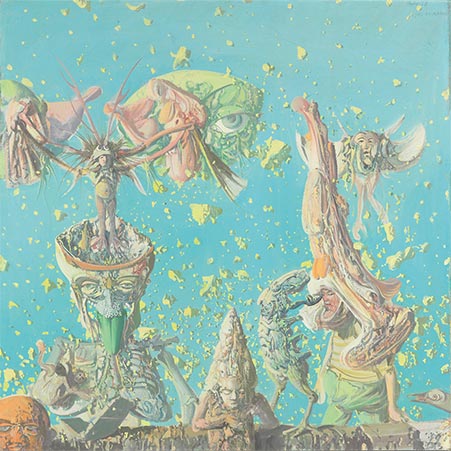

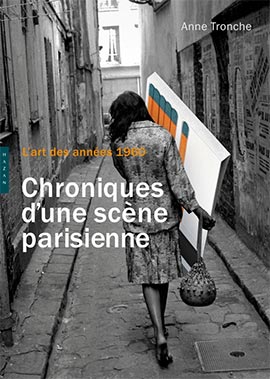

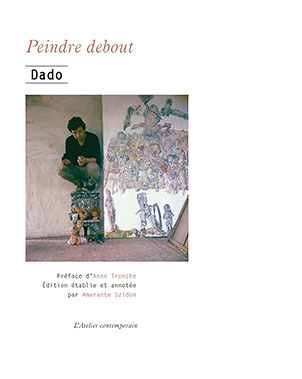

Dado by Anne Tronche

Beaches and Butchery

Extract from the remarkable article by Anne Tronche (1938-2015) that appears in her book, L’Art des années 1960. Chroniques d’une scène parisienne (Paris, Hazan, 2012, p. 160-167). We also owe to Anne Tronche the exemplary foreword to the anthology of conversations with Dado published by L’Atelier contemporain under the title Peindre debout.

Click on the images to enlarge them

(large and extra large sizes)

❧

Fullscreen

slideshow

Photo: Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky – Fonds Vera Cardot et Pierre Joly.

I was gazing at the brogue moccasins squishing through the mud that rainy November morning, when he rushed out, hair dishevelled, his dark clothes slashed with multicoloured paint. We were at Hérouval, in Dado’s domain, surrounded by carcasses of objects, by oddly heaped bones, the whole organized into an unlikely landscape of dissolution vaguely redolent of an open-air scrap-metal yard. Dado’s dealer, André-François Petit, had kindly offered to accompany me on this first visit to see the Montenegrin artist. As was his wont, Petit had chosen an elegant get-up and his fine shoes were fighting a losing battle against the encroachments of the muddy, brown earth. This seemed to amuse the artist, who, with a twinkle in his eye, saw in the conflict between elegance and the organic reality of the boggy soil a kind of image of the relationship between the civilized mind and the savage mind. In Civilization and its Discontents, Sigmund Freud advances the hypothesis that our civilization is bound up with the demotion of the sense of smell, with a disgust for pungent odours; one might add that our fear of things that sully, our repulsion for the formless, has also gone hand in hand with the progress of urban life. In all probability, it was such considerations that occupied Dado’s mind as he led us off towards a covered shelter. In this damp period of the year, inside the first range of buildings that contained the communal spaces, it was far from warm, as the doors were frequently thrown open to let in a child, a cat, a chicken.

Photo: Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky – Fonds Vera Cardot et Pierre Joly.

[…] [S]eeing my eye light on a mattress lying in a cupboard below the studio stairs, Dado informed me that it served as a bed for one of his sons. In such a poorly heated workshop, it looked at the very least uncomfortable. It exemplified a Spartan way of life, like that of our ancestors out in the far-flung countryside. His expression told me that he half expected our astonishment, or something still more, reducing us, André-François Petit and myself, to sell-outs to consumer society. Doubtless his penchant for all that is rudimentary meant he could reinstate values long decried by our Western societies and to assemble around him a space where real, personal life, where pictorial experience and the history of ideas were closely intertwined. Dado subjected everything around him, the fly-tips around the house, every habitable space, while his passion for waste set up relationships that turn the very idea of independent artistic activity on its head. His obstinately treating his domain in this manner stems from the very essence of his work; from its highly individual way of invading a site, of placing the walls and the floor under its authority, of tattooing every prosaic object the studio contains. As if the workshop is not only the backdrop for what is made there, but also the purveyor of its motifs. Save for when he sets to work decorating the walls of a deserted chapel, Dado has remained in Hérouval, amid these glorious if precarious traces, some of paint, some of drawing, some of scratches, some of objects. The fire in his studio in 1989 has not apparently altered his working methods and a number of smoke-blackened or charred objects had once again been integrated into the environment. His indifference with respect to whatever appeared to him not of absolute necessity, his lack of concern with the least modicum of comfort, which can readily be interpreted as arising from a hostility to the demands of wellbeing, are probably much more complicated. I see them rather as echoing the position adopted by [Maurice] Blanchot with regard to the goals of art: “to uphold, to fashion our nothingness?”

Translated from French by D. Radzinowicz

Photo: Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky – Fonds Vera Cardot et Pierre Joly.

Photo: Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky – Fonds Vera Cardot et Pierre Joly.